INTRODUCTION

Many universities struggle to encourage academic teachers to engage in the scholarship of teaching and learning (Boyer, 1990) for reasons of, for example, lack of time for educational development (Elmberger, Björck, Liljedahl, Nieminen, & Laksov, 2019), lack of perceived value in promotions (Bolander Laksov, 2018), and whether or not award schemes have been implemented at institutional level (Winka, 2017). Hence, in Sweden and other countries, universities have introduced local funding schemes to secure proper funding for such projects (Burdick, Friedman, & Diserens, 2012). Two problems with local funding, however, are that these projects often result in knowledge not being shared or built upon, and that individuals advocating change in their organisations meet resistance they cannot overcome and so either give up, or continue working for change in isolation (McGrath, Roxå, & Bolander Laksov, 2019). At Stockholm University we tried to solve this problem, as well as a current problem of few experienced educational developers and weak ties to the many (sixty at the start of the programme) departments, by designing a programme we called the ‘Pedagogical Ambassadorship Programme’. The idea was for departments to apply for funding for established academics to spend 20% of their working hours as pedagogical ambassadors for one year. This is the account of how the programme was designed and its outcomes as revealed in a web survey after being in operation for four years.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

We chose to call the programme pedagogical ambassadorship, as it signifies not only that the programme is focused on education, but also on pedagogy in line with Murphy (2008, p. 38): pedagogy strives to increase the quality of the ‘interactions between teachers, students, and the learning environment and the learning tasks’ (Murphy, 2008, p. 35). The word ambassador was used because ambassadors are promoters of certain activities with a mandate, and are permanent representatives of pedagogy in a different ‘country’ (i.e. their department), where non-pedagogical values may be at the forefront. The pedagogical ambassadors were thus expected to work with pedagogical development in and of their departments, in collaboration with the Educational Development Unit (EDU) of the university.

CONTEXT

The Pedagogical Ambassadorship Programme was piloted in 2015 at the Faculty of Humanities, with two projects focusing on development of student academic literacy and alignment in assessments, and then scaled up to include all four faculties of the university in 2016. At the outset of the programme, it was part of the strategy to build competence and capacity for educational development at the EDU which had recently experienced a reorganisation and was lacking in academic development staff. Five years after the programme started the EDU group has grown from six to nearly 50 people, many of whom are former pedagogical ambassadors who spend 5–20% of their working hours within the unit holding or teaching courses, as members of our editorial group who produce a research newsletter, and holding regular workshops on topics like plagiarism, assessment, generic skills, flipped classroom, etc.

THE DESIGN OF THE PEDAGOGICAL AMBASSADORSHIP PROGRAMME

With the purpose of encouraging or pushing or influencing departmental and institutional culture towards a more scholarly approach to teaching and learning, the pedagogical ambassador programme aims to: (a) focus on the development of educational culture, (b) engage senior management in the bid process, and (c) create a mandate for change for the ambassadors. An explicit focus of the programme is to establish communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) around teaching and learning at the departmental level, through the facilitation of local educational conversations and brokering of higher education research into the department. Accordingly, more than half of the projects included the introduction of lunch seminars, workshops, or other arenas for sharing experiences and practices of teaching and learning.

Previous research has shown the importance of legitimacy for agents of educational development (Clavert, Löfström, Niemi, & Nevgi, 2018). Hence, it is important to attract legitimate members of the departmental practice to the programme – people who are viewed by colleagues as insiders rather than outsiders. The pedagogical ambassadors need to have an understanding of the organisation’s requirements and a network of colleagues to help create a broader ownership of the project at the department. So far, many – but not all – of the pedagogical ambassadors have been directors of studies, positions that indeed provide some formal legitimacy.

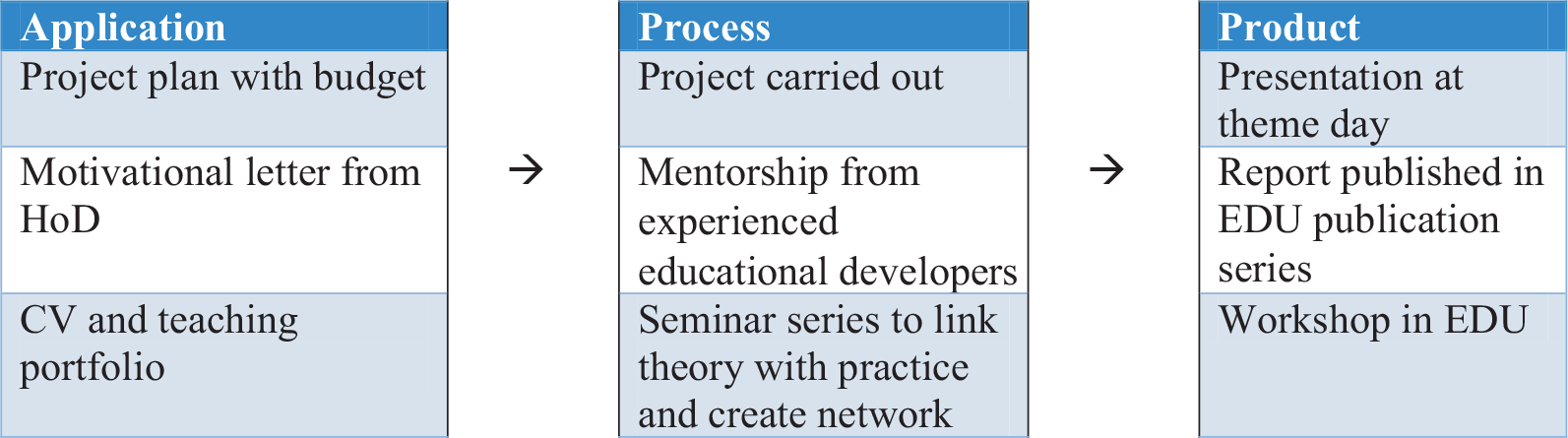

With the aim of adapting to the needs of the departments, interested individuals are encouraged to ground their project proposal of one year in a departmental group before submitting it, attaching a budget of maximum SEK 250 000 sek to pay for 15–25% of Pedagogical ambassador’s time depending on salary. Heads of departments (HoD) are required to submit a motivational letter as part of the application, outlining the benefits of the pedagogical ambassadorship to their departments. They are also kept updated with information and are regularly contacted by the EDU Director by email, explaining the important role they have for the success of the ambassadorship project. Specifically, the heads of departments are asked to make the ambassadors visible in their departments, showing support and providing a place and space for them at internal meetings and departmental away-days. CV and teaching portfolio of the applicant are also submitted.

Applications (Figure 1) are assessed according to the following criteria:

• the quality of the project proposal;

• the teaching portfolio of the applicant;

• their relevance to the department as stated in motivational letter from HoD; and

• their relevance to other university departments.

At the beginning of the year, successful applicants are asked to present their projects and discuss them with experienced educational developers. In addition, ambassadors are assigned an experienced educational developer as a mentor for continuous support throughout the process, with expertise in educational development and educational research, which means that mentors should be active in both those areas. To supplement this, a seminar series provides a shared space for linking practice with higher education theory, including literature on how to deal with the implementation of educational change as this is an issue previously identified as a challenge (McGrath, Roxå, & Bolander Laksov, 2019).

Pedagogical ambassadors are asked to present their ongoing work to get feedback halfway through the programme at the EDU kick-off in August, and again on a ‘theme day’ in December to a wider audience including departmental heads and other interested academic staff. The project is also presented in a report published in the EDU publication series. At the end of the ambassadorship year, all ambassadors are invited to organise a workshop for university teachers at the EDU, as a way to generalise the outcomes to a wider audience of academic teaching practices.

EVALUATION

A web-based survey was designed, asking pedagogical ambassadors to rate the value of the programme to their personal development and to their department as a whole on a scale of 1 (no value) to 10 (highly valuable). The survey was distributed to everyone who had been a pedagogical ambassador between 2015–2018 (n = 28). Seventeen individuals answered the questionnaire, which represents a 60% response rate. They valued their time as pedagogical ambassadors highly, giving a mean rating of 8.7 out of 10. The average value of how the ambassadors estimated the value of their contribution to their departments was 6.9 – slightly lower but still clearly valuable.

The survey also asked ambassadors to write their main arguments explaining why the university should continue to fund educational ambassador projects. In summary, the responses suggest that pedagogical ambassadorships are important for several reasons. For example, it was pointed out that the strong link to local practice, where educational development comes from within the department, is bottom-up, not top-down, and enables the engagement and motivation of academic staff in the development of teaching. It also leads to the strengthening of pedagogy, which had received increased attention in some of the departments. Responses suggest educational development is a matter of teaching quality and something that all departments need, but they also need support in developing educational practice as this is not something most academics have expertise in. Finally, it is clear that pedagogical ambassadorships create a clear role with a mandate, space and time for work that can otherwise be set aside, but which is necessary for an institutional approach to educational development where collaboration between departments around education is usually neglected.

EXPERIENCES AND LEARNING POINTS

Based on the experience of having run the programme for five years, the following reflections can be made regarding the conditions, challenges and opportunities for a successful programme.

It seems clear that ambassadors who start from a formal position, such as director of studies, have an advantage in terms of a platform to work from. However, this is not enough in terms of taking an educational leadership (Bolander Laksov & Tomson, 2017) to work with cultural change around teaching and learning at departmental level. The communication strategy from the management of the department is also of the utmost importance, and the pedagogical ambassador needs to keep up an on-going dialogue with their department head to make sure the project is viewed as a shared project for the department – not an individual project.

The other important on-going dialogue is between the ambassador and the EDU. Unlike other educational development projects funded by the university, the pedagogical ambassadorships build a partnership between the department and the EDU via the pedagogical ambassador. Hence, the EDU needs to keep on inviting the ambassadors to participate, asking for views and advice, and including the pedagogical ambassadors in their activities to show that what they bring to the EDU is valuable and desired. It is through the establishment of such acknowledgement that a trusting relationship between the EDU and the departments can be established, and the educational culture has a chance to develop to include more emphasis on scholarly approaches to teaching and learning and sharing of teaching practices. The relationship between educational culture and pedagogical ambassadorship is, however, an area that needs further exploration.

Finally, it has become clear that a challenge for the pedagogical ambassadors is time. Repeatedly, we have seen the difficulty of keeping daily tasks at bay – and perhaps this is even more challenging for the director of studies. Some coaching in time management could be a solution, but a strong link to departmental management and a local team of interested and engaged colleagues is probably more important.

REFERENCES

- Bolander Laksov, K. (2018). Lessons learned: Towards a framework for integration of theory and practice in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 1–12.

- Bolander Laksov, K., & Tomson, T. (2017). Becoming an educational leader–exploring leadership in medical education. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(4), 506-516.

- Burdick, W. P., Friedman, S. R., & Diserens, D. (2012). Faculty development projects for international health professions educators: Vehicles for institutional change? Medical Teacher, 34(1), 38–44.

- Clavert, M., Löfström, E., Niemi, H., & Nevgi, A. (2018). Change agency as a way of promoting pedagogical development in academic communities: A longitudinal study. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(8), 945–962.

- Elmberger, A., Björck, E., Liljedahl, M., Nieminen, J., & Laksov, K. B. (2019). Contradictions in clinical teachers’ engagement in educational development: An activity theory analysis. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 24(1), 125–140.

- McGrath, C., Roxå, T., & Bolander Laksov, K. (2019). Change in a culture of collegiality and consensus-seeking: A double-edged sword. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–14.

- Murphy, P. (2008). Defining pedagogy. In K. Hall, P. Murphy & J. Soler (Eds.), Pedagogy and practice: Culture and identities. London: SAGE publications.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system. Systems Thinker, 9(5), 2–3.

- Winka, K. (2017). Kartläggning av pedagogiska meriteringsmodeller vid Sveriges högskolor och universitet [Mapping models of teaching awards in swedish Higher Education Institutions]. PIL-rapport, University of Gothenburg.