INTRODUCTION

This study sets out to investigate the composition of teaching and research staff at Swedish universities and to discuss the findings in relation to internationalization and diversity. Internationalization has begun to dominate the agendas of policymakers in higher education (Huang et al. 2014). In relation to students, internationalization is motivated by economic and political aims. On the other hand, internationalization is also seen as an instrument to improve the quality of education and as a means to provide students with intercultural competences (de Wit et al. 2015). In policy documents, internationalization is often described as a prerequisite for the quality in education and research, where incoming students and researchers are viewed as an asset in the teaching and research environments. International students and researchers are expected to enrich the research projects and discussions in classrooms with new perspectives. They are also seen as strengthening the international environment and diversity, which are expected to promote the understanding of other cultures and traditions (Swedish Government Commission 2018; Bryntesson & Börjesson 2019).

In terms of teaching and research staff, academic labor markets have become increasingly global. Especially the policies to promote the internationalization of research are often closely related to discourses of excellence, with links to universities’ recruitment policies that aim at attracting international talent from abroad (Huang et al. 2014; Pietilä 2015). The quest for excellence via the recruitment of international researchers is clearly expressed in Swedish higher education policies (Swedish Government Commission 2018).

Globalization and internationalization call for a re-examination of how different groups are included in higher education. Higher education research has long been engaging with questions of diversity (McNair et al. 2020; Shavit et al. 2007) underlining the structural imbalances and the institutionalized nature of inequalities (Bhopal & Maylor 2014). International research indicates structural inequality in academia where women and ethnic minorities have lower chances for upward career mobility and professorships (Hofstra et al. 2022). Research from the United Kingdom indicates that foreign-born staff are found especially in the lower career positions in universities (Bauder 2015; Smetherham et al. 2010; Khattab & Fenton 2016). Previous research also indicates that the opportunities to be internationally mobile are gendered with women facing more challenges to be mobile (Vabø et al. 2014; Jöns 2011; Morley et al. 2018).

Due to increasing variety in ethnic backgrounds among the populations in many countries, universities are more than ever paying attention to issues related to diversity and inclusion (Byrd et al. 2019). Until now, diversity in Swedish higher education has been discussed mainly in relation to student populations, while the composition of teaching and research staff has been of less policy concern. This is although previous research indicates that researchers with immigrant backgrounds, in particular those from Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America, have slower career progression and face higher risks of unemployment in Swedish academia compared to native staff (Behtoui & Leivestad 2019). In Norway, a recently published overview of the research personnel employed in the Norwegian research sector (Steine 2023) found out that individuals born in Norway with foreign-born parents were underrepresented in the Norwegian research sector when compared to the whole population. There is a call especially for intersectional approaches to study in what positions female and male researchers from abroad and with an immigrant background are found in Swedish academia.

Although the composition of teaching and research staff is a fruitful topic in the study of social inclusion, it has remained largely a missing angle in internationalization and diversity discussions in the Nordic higher education and research sector, including Sweden. There is a lack of research on the internationalization and diversity of teaching and research staff at Swedish universities. Apart from a few important exceptions, such as the studies by Mählck (2013) and Behtoui and Leivestad (2019), few recent studies have explored the Swedish academia’s inclusion of teaching and research staff who were born in Sweden but have a foreign background; individuals who are typically not the targets of internationalization policies.

This paper aims to fill part of this research gap. We study the development of the composition of teaching and research staff in three key job categories in Swedish universities: career development positions, lecturerships, and professorships. Our time frame for the analysis was eleven years (2008–2018). The investigation is a continuation of a previous study on the internationalization of universities’ teaching and research staff in three Nordic countries: Sweden, Norway, and Finland (Pietilä et al. 2021). In this paper, we argue that it is relevant for studies on internationalization and diversity to make a clearer distinction within the staff with an international background, and to analytically separate the researchers who have come to the country mainly for the purposes of studies or work (internationally recruited researchers) and the researchers born in the country, but with an immigrant background (descendants of immigrants). We argue that staff compositions are one way of estimating the equality of job opportunities in academic career progression and universities’ inclusiveness as organizations. In accordance with the intersectional approach, we also ask how the background of staff is interrelated with gender.

Research has shown that there are disciplinary differences in the traditions and requirements for mobility (Cañibano & Bozeman 2009; Herschberg et al. 2018). Thus, we compare the main results between the major fields of academic sciences by grouping them into two broad categories: the hard sciences (natural sciences, mathematics, agricultural sciences, engineering and technology, and medical and health sciences) and the soft sciences (social sciences and humanities).

THE RELATION BETWEEN INTERNATIONALIZATION AND DIVERSITY

The concepts of internationalization and diversity are related but different. Internationalization refers to the intentional processes of the policies and practices undertaken by academic systems and institutions to cope with the global academic environment (Altbach & Knight 2007). The term pertains to broad changes in universities, such as the recruitment of international researchers, the mobility of students and staff, research collaboration, and institutional partnerships (Altbach & Teichler 2001; de Wit et al. 2015). In policy papers, the attraction of international scholars is often associated with positive connotations. The Swedish government policy has strongly emphasized the need for increased internationalization and mobility in higher education (Swedish Government Commission 2018; Swedish Government Commission 2017, Swedish Government Bill 2020). Internationalization is especially in the focus in relation to academic recruitment criteria and career advancement (Swedish Government Bill 2020, 73).

If internationalization stands for opportunities, diversity is more about solving existing problems. It is more often used to describe how minority groups already residing in the country are included in the labor market and accommodated in the organization. Diversity management refers to voluntary initiatives directed toward the systematic recruitment and retention of employees belonging to diverse social identity groups (Konrad et al. 2005, 2). The focus is often especially on the inclusion of groups that have in the past been systematically oppressed or discriminated against (Hays-Thomas 2004). Diversity may refer to different things. It can refer to the representation of different minority groups (based on, for example, gender, race, ethnicity, disability, or sexual orientation) in a country or organization, or it can refer more broadly to how those differences are valued and respected (Konrad et al. 2005). In the Swedish context, diversity has primarily been discussed in terms of ethnicity or foreign background. It has been strongly associated with the idea that the representation of a wide range of groups can contribute to increased cultural awareness and a multicultural environment (Swedish Government Commission 2000).

Contrary to internationalization, the concept of diversity includes a social justice aspect. Diversity is considered something good that can contribute to enhanced quality in education and research. Castiello-Gutiérres (2019) argues that the policy on internationalization has shifted from being perceived as a form of intercultural cooperation to a narrative closer to excellence rhetoric and market interests. In this way, internationalization attempts seem to be driven by an ambition to bring in research excellence (Herschberg et al. 2018; Morley et al. 2018), while the goals towards diversity aim at creating a multicultural environment on campus.

Despite these theoretical differences, the use of the two concepts is fuzzy as they are often used interchangeably and in an overlapping way (Mählck 2018). Internationalization of higher education is expected to bring in students and staff from different backgrounds and in this way contribute to diversity. In line with this, diversity is used as a strong argument for internationalization (Langford et al. 2019; Swedish Government Commission 2000; 2018). Horst and Erdal (2018, 2) argue that the concept of diversity includes “different types of people, such as people of different races or cultures, in a group or organization”. This makes the use of the term problematic when referring to international researchers because in many cases, foreign researchers are recruited from countries that are politically and culturally related to Sweden (cf. Swedish Higher Education Authority 2020; Amirell 2021; Erdal & Midtbøen 2018). From a post-colonial perspective, critical scholars have argued that neocolonial relations continue to influence research policy (Takayama et al. 2016) and that internationalization in many ways rather means westernization (Sperduti 2017).

Thus, the concept of diversity often masks ambiguities in terms of who we are talking about. In research, we therefore need to distinguish between different groups. Native Swedes, international researchers and descendants of immigrants are likely to be recruited in different ways and to find different opportunities for promotion.

DATA AND METHOD

This study focuses on Sweden, a country which has become more ethnically diverse in recent decades. In 2021, the share of people with a foreign background was 26% (13% in 1995). This includes individuals who were born outside Sweden, 20%, and individuals who were born in Sweden with two parents born in another country, 6% (Statistics Sweden 2021).

In most EU countries, native-born people with immigrant parents are underrepresented in higher education (OECD 2017). This is not the case in Sweden anymore. In parallel with the changing composition of the Swedish society, the share of students with foreign backgrounds has also increased. In 2019, 26% of entrants into higher education had a foreign background, whereas in 2009 the share was 17% (Statistics Sweden 2020). Students with a foreign background (49%) start higher education more often compared to students with a Swedish background (45%). In doctoral education in the academic year 2020/2021, the share of entrants with a foreign background who were permanently living in Sweden prior to their doctoral studies was 16%. The share of international doctoral students who arrived in Sweden to study was 40%, and the share of doctoral students born in Sweden was 44% (Statistics Sweden 2022).

In this study, we use data from Statistics Sweden. In its reports, Statistics Sweden usually uses the term “staff from a foreign background” (utländsk bakgrund) to refer to two different groups: a) individuals who were born outside Sweden and b) individuals who were born in Sweden but who have two parents who were born in another country. In the case of teaching and research staff, we think it is important and interesting for research purposes to make a clearer differentiation within this group. For example, there may be gender differences within the group of staff with a foreign background.

In our analysis, we differentiate four main groups:

- teaching and research staff born in Sweden and with two parents born in Sweden,

- teaching and research staff born in Sweden and with one parent born in Sweden and one parent born outside Sweden,

- teaching and research staff born in Sweden with two parents born abroad, and

- teaching and research staff born outside Sweden.

Researchers born outside Sweden are likely to include mostly internationally recruited staff who came to the country for study or work purposes (Swedish Government Commission 2000). However, it should be pointed out that we do not know the reasons or timing of immigration. This group is herein referred to as “foreign-born staff” or “international staff”. The group of staff born in Sweden with two parents born abroad are herein referred to as “descendants of immigrants.” We acknowledge that the groups are internally heterogeneous with different causes and timing of mobility, and with a diversity of geographical backgrounds (see Behtoui & Leivestad 2019). As the dataset available did not include any information on the countries or regions of origin (e.g., western/non-western), in this paper we are only partly able to address the complex issue of internationalization and diversity. We argue that the division still provides a reasonable first overview of the distribution of staff with a foreign background in the academic sector. Further research could use more fine-grained data with information on the countries of origin, reasons for mobility, and career trajectories.

The dataset includes all teaching and research staff employed at Swedish universities between 2008 and 2018. For this paper, we used data on staff in three major groups of academic positions at Swedish universities: a) career development positions (meriteringsanställningar), including postdoctoral researchers, assistant professors, and research assistants (that require a PhD), b) lecturers (lektorer), and c) professors (professorer). All data are presented in headcounts (the data include both full-time and part-time staff). The dataset is missing information on the origin of some staff, especially in the group of professors (e.g., in 2018, the share of missing information was 4.2% of all professors). We removed these data from the graphs.

We expect to see changes in the staff compositions especially among career development positions. This is the career phase when mobility is typically most pronounced. In addition, career development positions are mainly research-intensive and do not typically require competences in the Swedish language. These positions are usually fixed-term, creating a higher turnover rate when compared to more senior-level positions, which are more typically permanent.

| Career development positions | Lecturers | Professors | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| women | men | total | women (%) | women | men | total | women (%) | women | men | total | women (%) | |

| 2008 | 852 | 975 | 1,827 | 46.6 | 3,021 | 4,386 | 7,407 | 40.8 | 893 | 3,848 | 4,741 | 18.8 |

| 2013 | 1,347 | 1,585 | 2,932 | 45.9 | 4,276 | 5,033 | 9,309 | 45.9 | 1,486 | 4,738 | 6,224 | 23.9 |

| 2018 | 1,813 | 2,137 | 3,950 | 45.9 | 4,975 | 5,563 | 10,538 | 47.2 | 1,860 | 4,740 | 6,600 | 28.2 |

Table 1 presents the number of individuals in the three job categories in three timepoints by gender. The job category of lecturers was the biggest one with 10,538 individuals in 2018, whereas career development positions was the smallest job category (3,950 researchers in 2018). It should be noted that the number of people in the positions has increased in all the job categories. It has especially increased among career development positions where the numbers have more than doubled in the time frame between 2008 and 2018.

During the time frame, the share of women in career development positions has remained quite stable at around 46%. Among lecturers, the share of women has increased by six percentage points (47% in 2018) and among professors by nine percentage points (28% in 2018).

In the analysis, we calculated the share of native-born staff with two native-born parents, native-born staff with one native-born parent and one foreign-born parent, native-born staff with two foreign-born parents, and foreign-born staff between 2008 and 2018, all combinations for women and men in career development positions, lectureships, and professorships. In the national statistics, gender is a binary variable that differentiates between men and women. Then we conducted a similar analysis focusing on the differences between the major fields of academic sciences (hard sciences and soft sciences) in career development positions. Additional graphs on lecturerships and professorships are presented in the Appendixes.

FINDINGS

Teaching and research staff in the three job categories

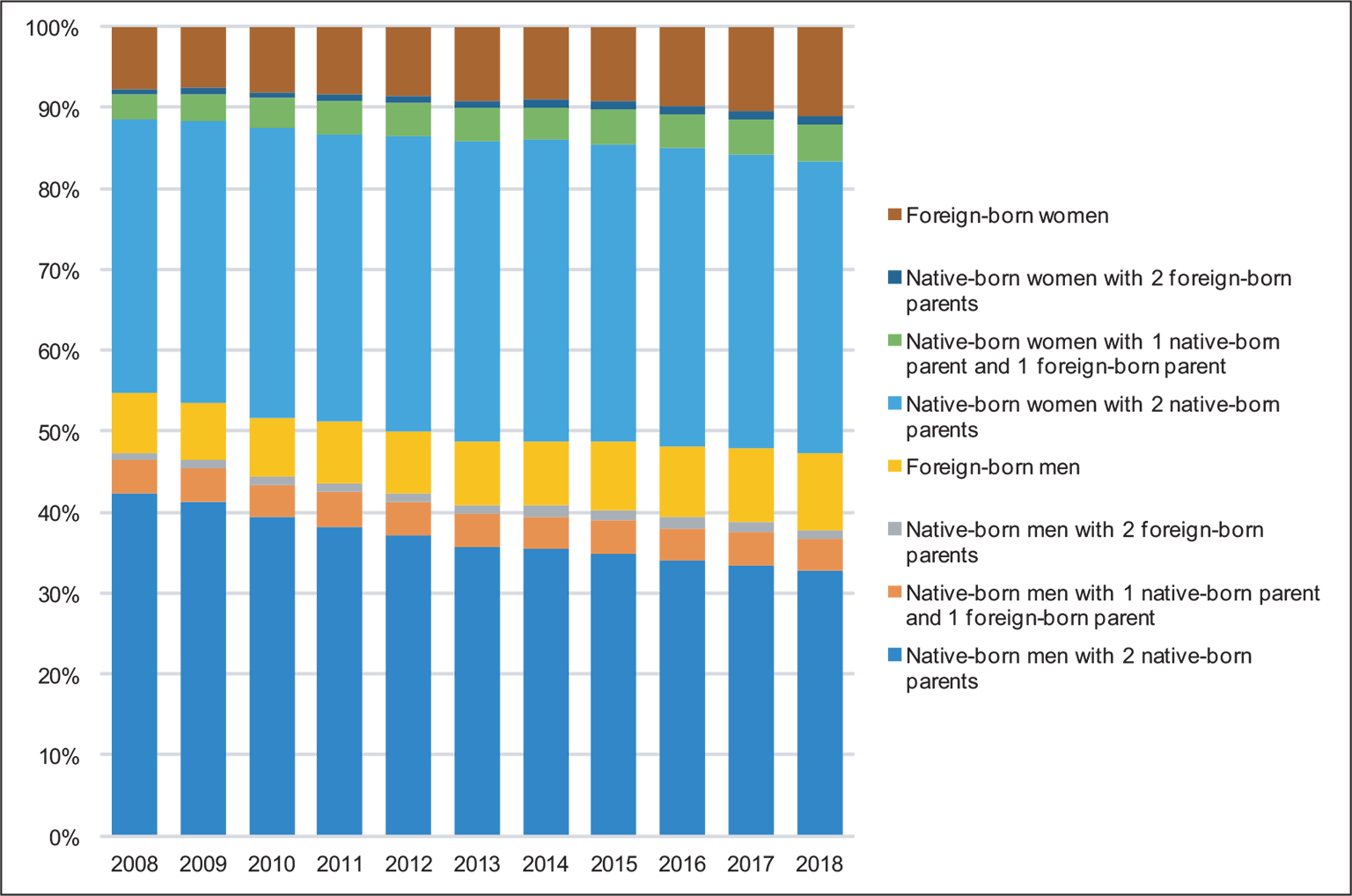

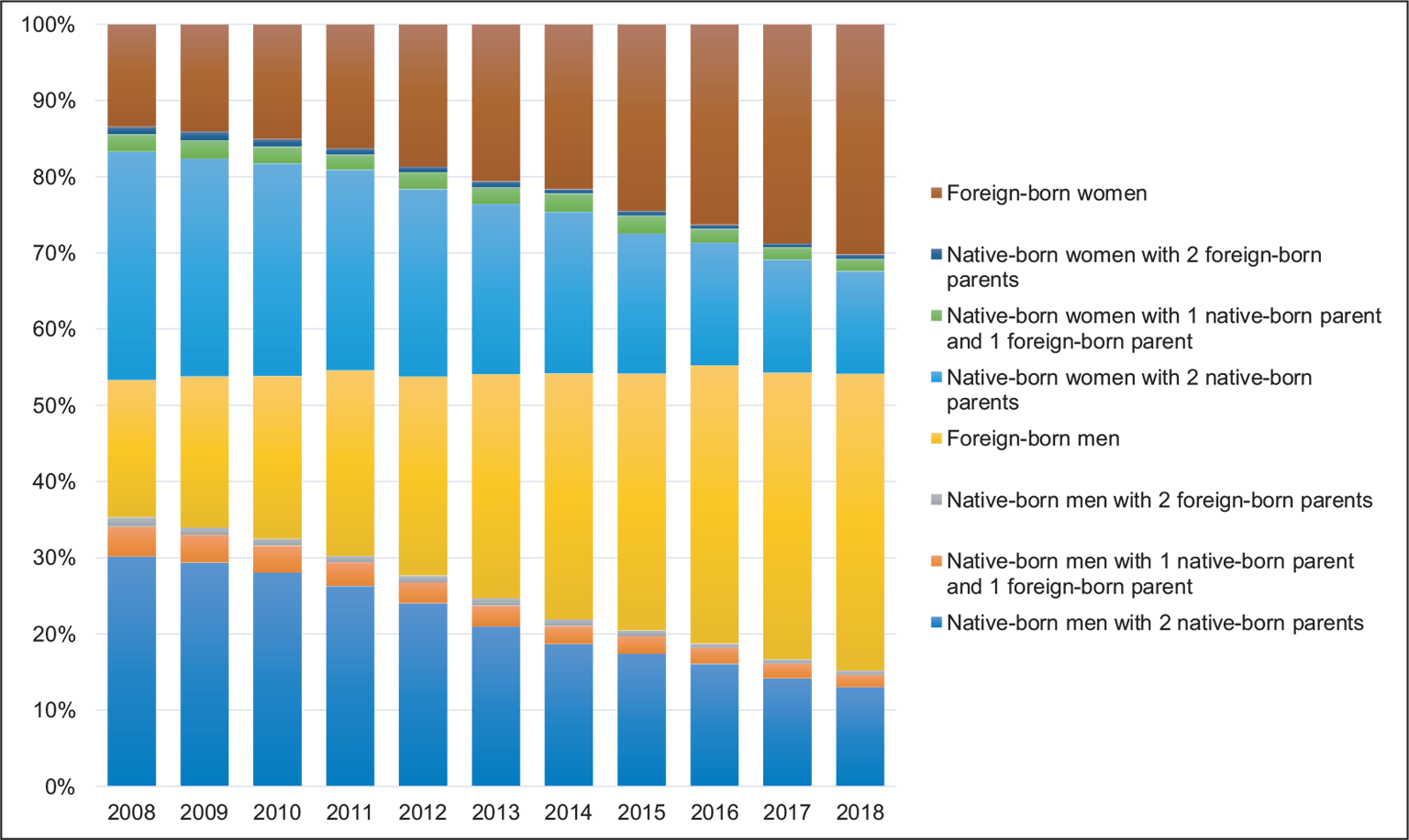

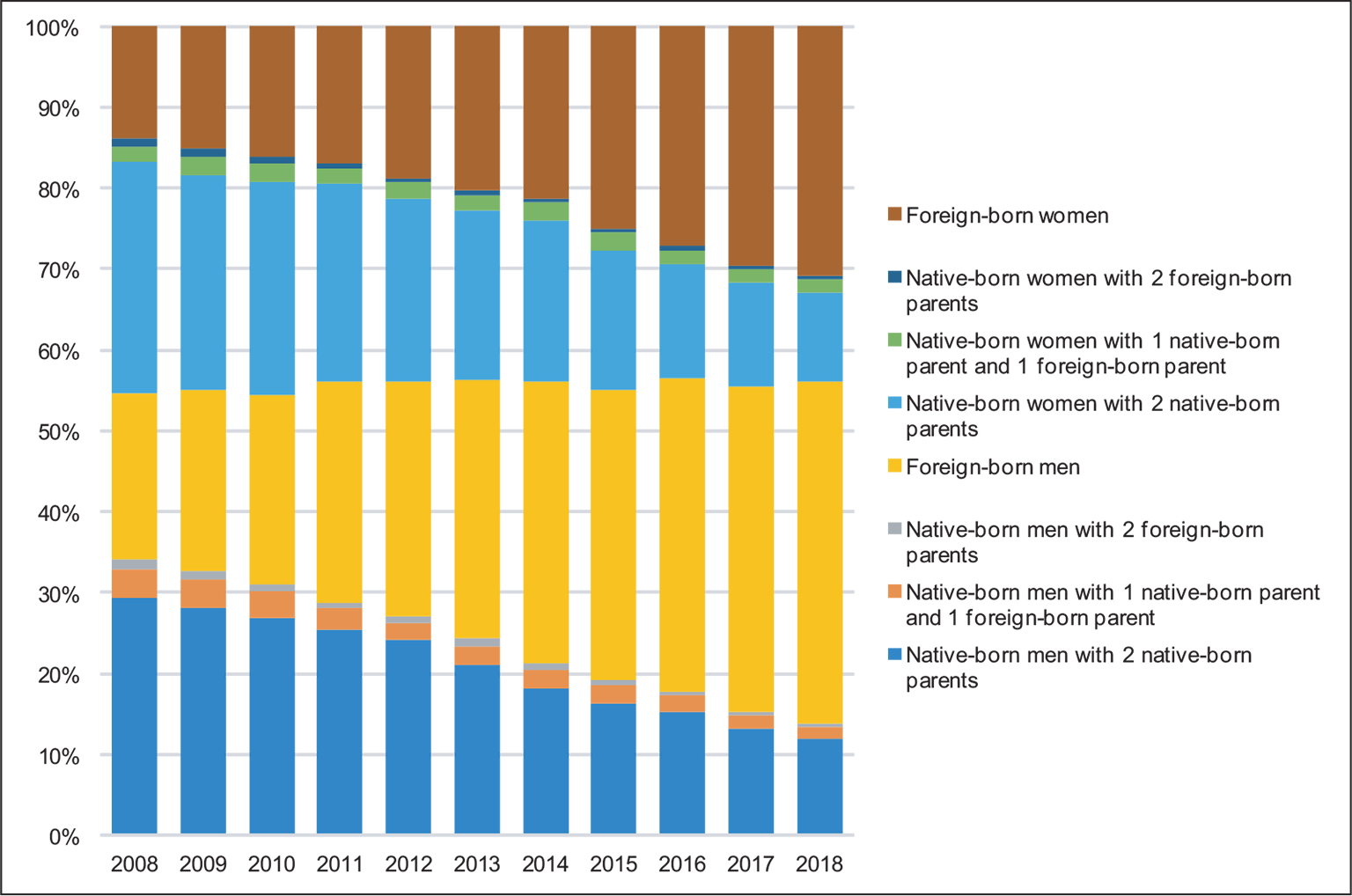

First, we investigated how the composition of staff has developed between 2008 and 2018 in career development positions. As we saw above in Table 1, the number of people in these positions has significantly increased in the time frame.

Figure 1 shows that there was a sharp increase in the shares of foreign-born staff, increasing from 31% of all staff in 2008 to 69% in 2018. Thus, in 2018 foreign-born staff were the clear majority in these positions. Accordingly, the share of native-born staff has decreased, and this is so for the staff representing all the three background compositions (born in Sweden with native-born parents, mixed parents, and foreign-born parents). The share of descendants of immigrants was one to two per cent of all positions with similar shares for women and men. The trends for both sexes are similar, with decreasing shares for both native-born women and for native-born men, and with a slightly steeper growth rate for foreign-born women than for foreign-born men. As was noted above, the share of women has remained quite stable at around 46%, so the increased share of foreign-born women has helped in keeping the gender balance quite even. The findings show that recruitment for career development positions in Swedish universities is today mainly international and that the universities have been successful in attracting both women and men scholars from abroad. There has been simultaneously an increase in the number of positions and an increase in the numbers of foreign-born staff (since 2011, there has been a decline in the absolute numbers of native-born staff).

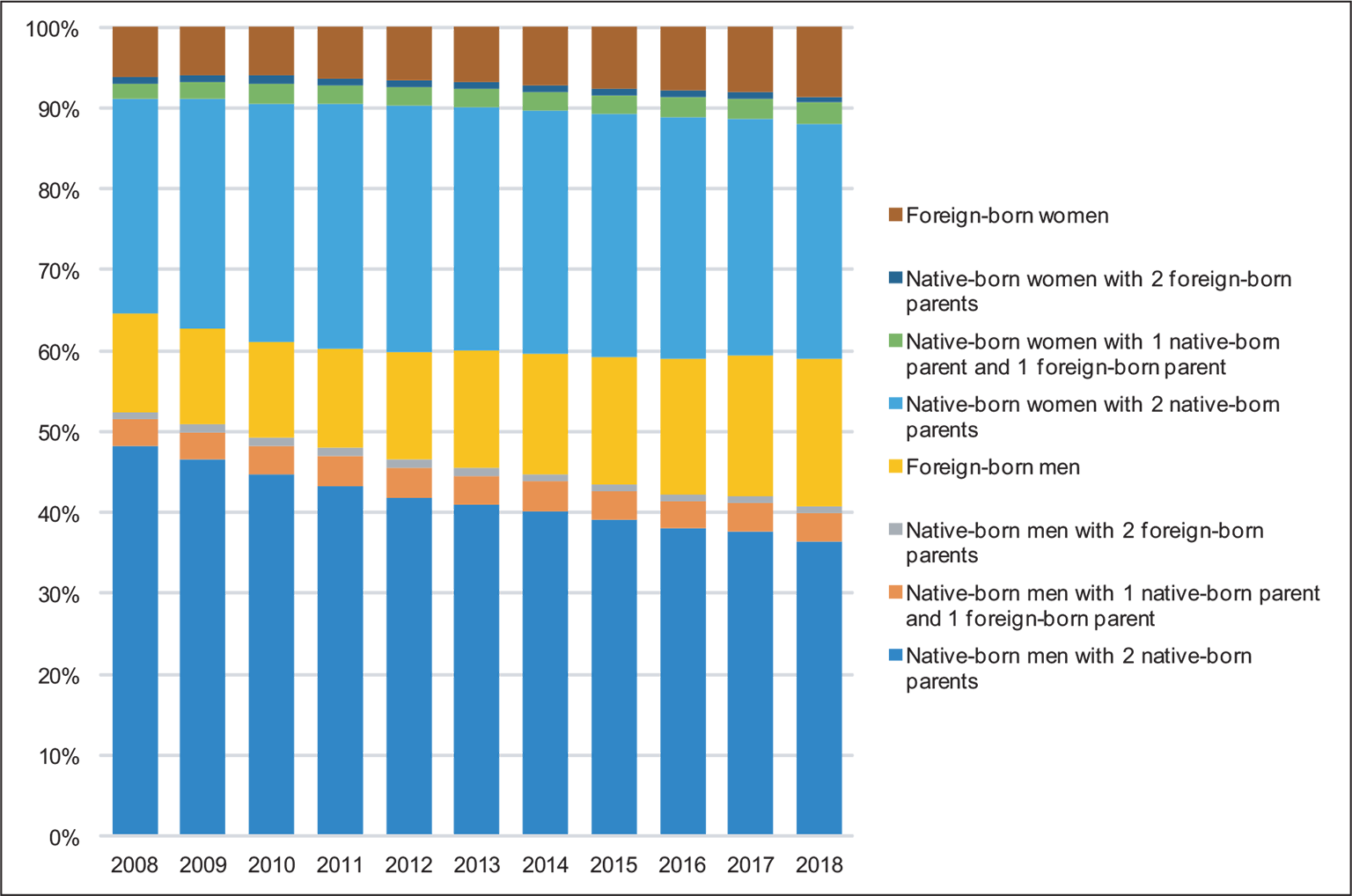

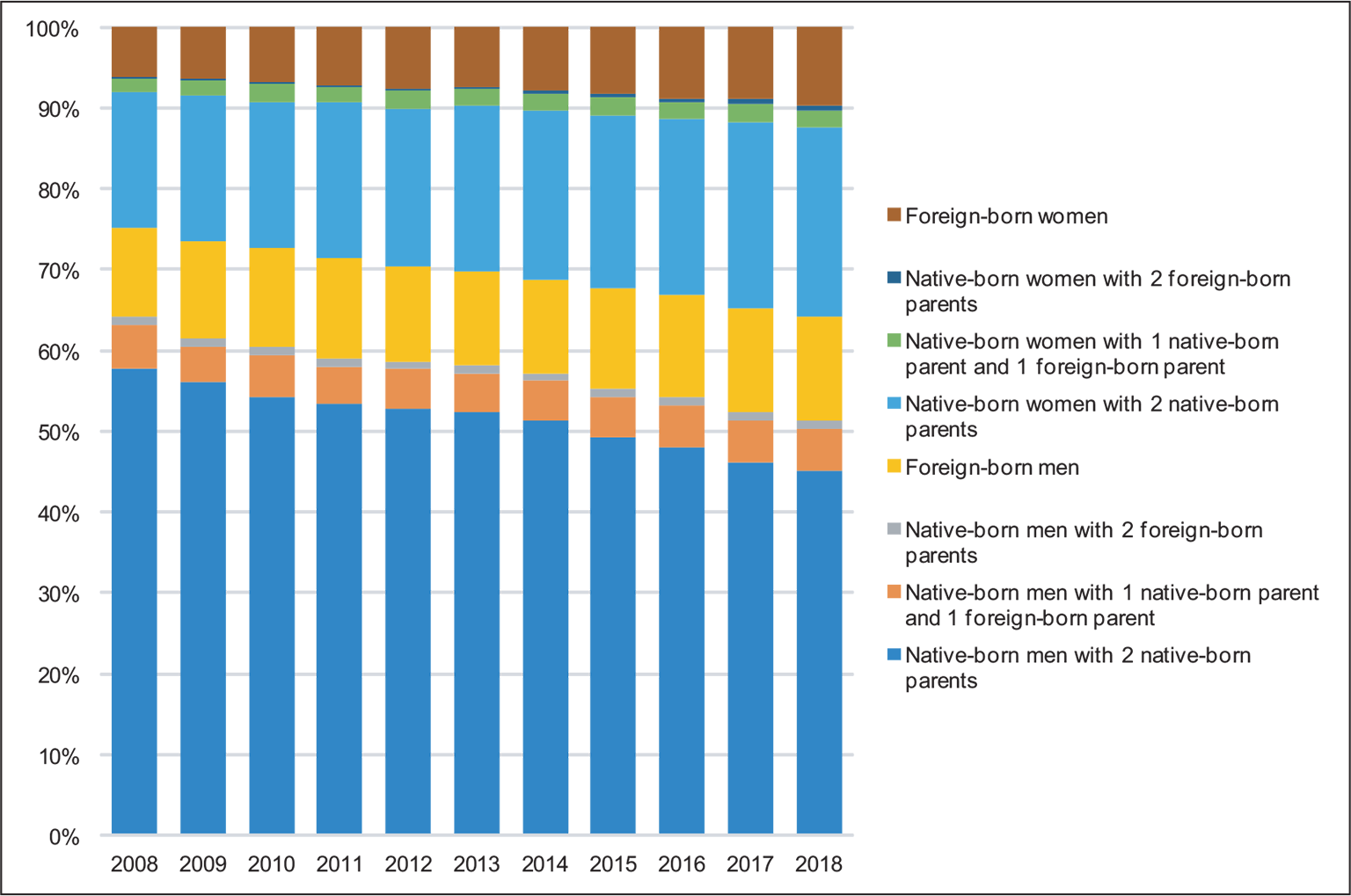

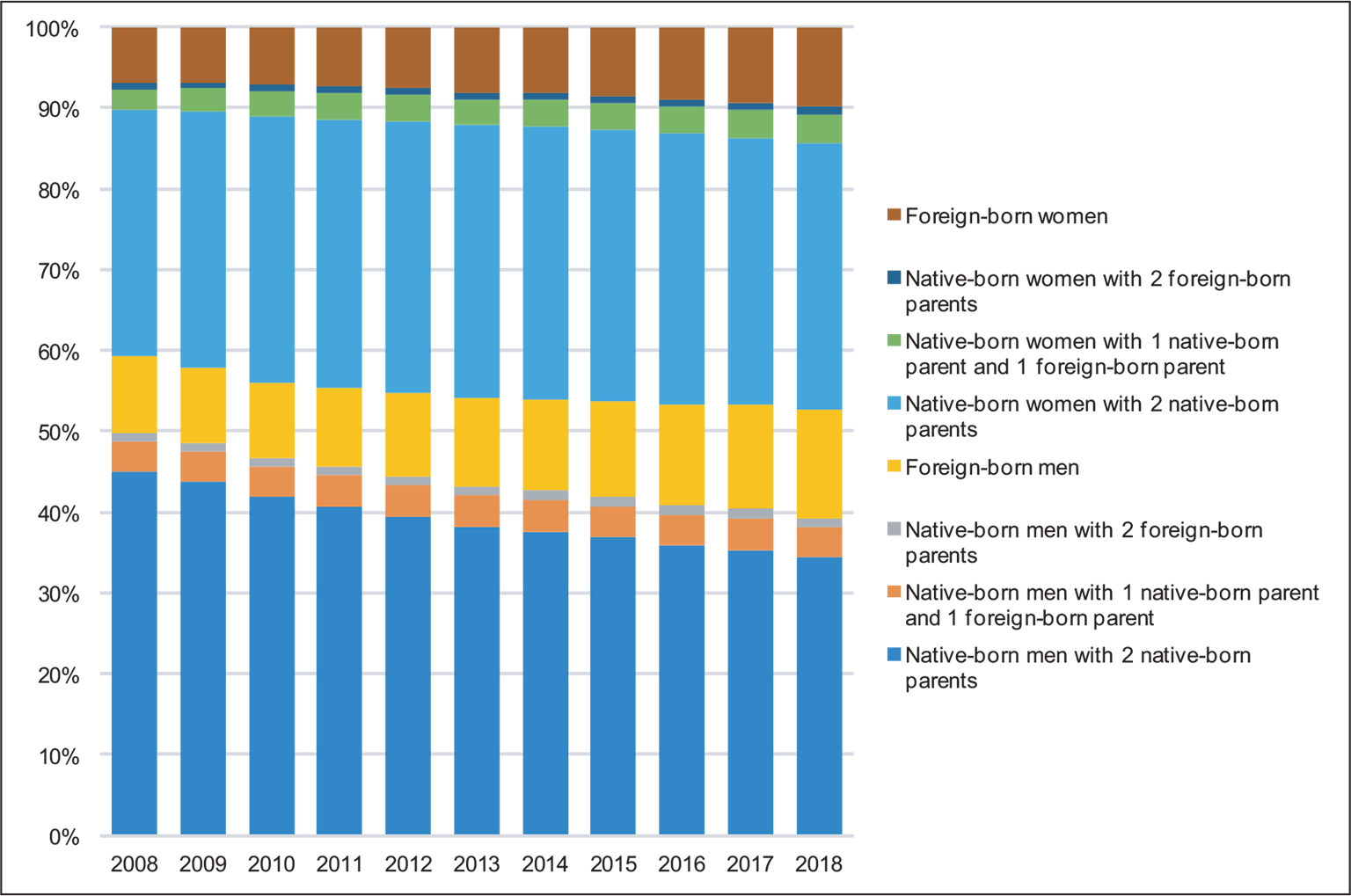

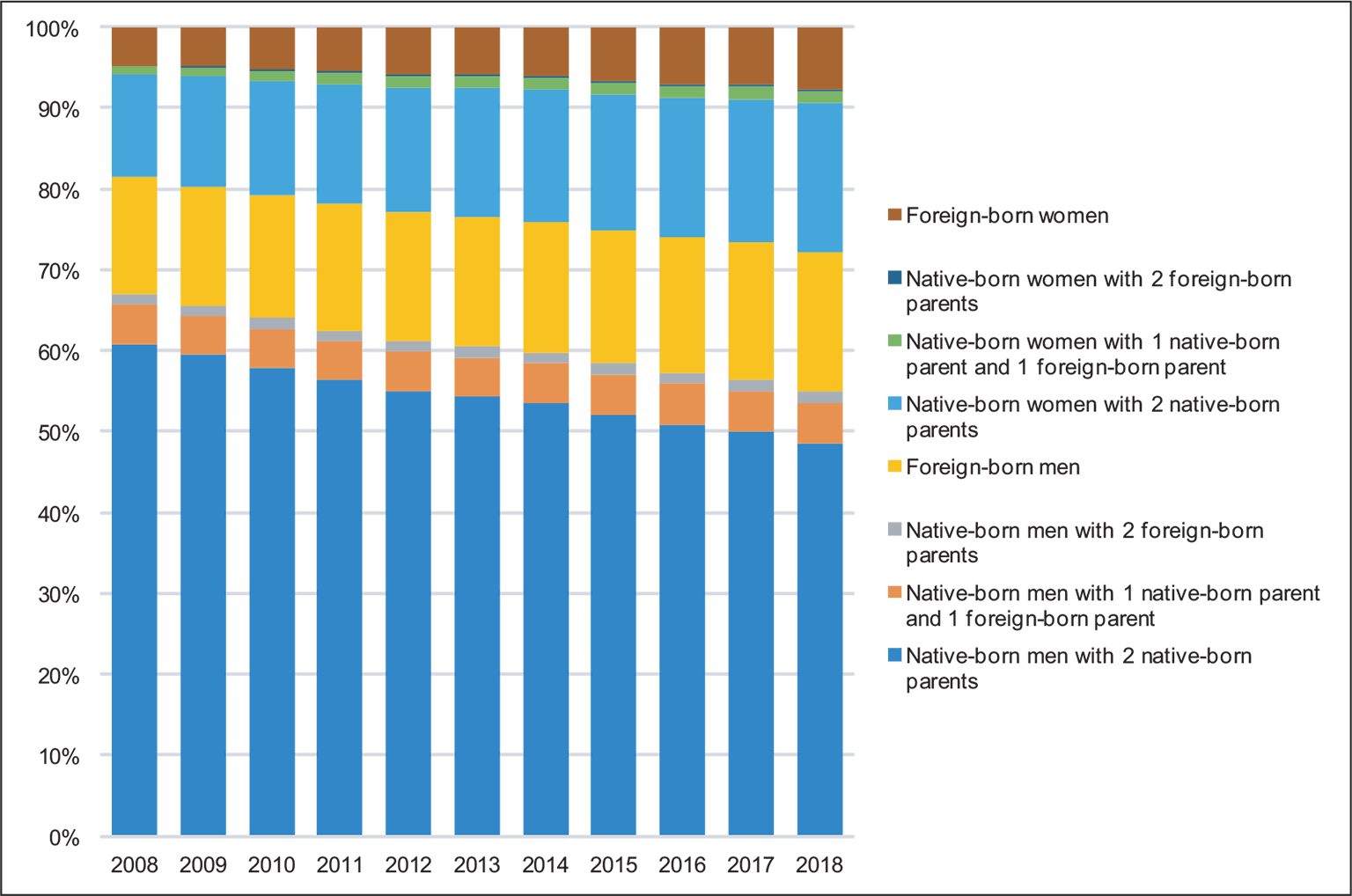

The following question is to what extent these changes are reflected in higher job categories. The next figures show that the share of foreign-born staff has increased also in the job categories of lecturers and professors, but not as steeply as in the career development positions.

Figure 2 shows that among lecturers, which is the dominant permanent teaching and research position in Swedish academia, the majority of staff were native-born with two native-born parents: in 2008, their share was 75%, and in 2018 67%. The share of foreign-born staff increased from 17% to 23%. The growth rates for foreign-born women and men are similar (42% for men and 41% for women). Descendants of immigrants represented approximately 2% of all lecturers, with slightly more men than women, and with only small changes in the time frame. Native-born staff with one native-born parent and one foreign-born parent comprised 6–7% of all staff with slightly more men than women.

Last, Figure 3 shows the equivalent developments in professor positions, the most prestigious positions in the academic hierarchy. Here, the share of foreign-born staff increased from 19% to 25%. What is discernible is the decline of native-born men compensated with an increase among native-born women, foreign-born women, and foreign-born men. The share of descendants of immigrants remained between 1.3 and 1.7%, the majority of them men. There is a gender difference in the group of individuals with mixed parents: native-born men with one foreign-born parent and with one native-born parent represented c. 5% of all professors, whereas the share of women with such backgrounds was c. 1–1.5% of all professors. However, the professor group includes a comparatively high number of missing observations, which is most likely emphasized in the groups with non-Swedish backgrounds. This implies that the findings for the smaller groups are not fully reliable or exact.

Overall, the results show that the big changes in the staff composition among career development positions are not reflected among lecturers and professors. This is important as the latter positions represent positions with higher status and job continuity. It remains to be seen if more changes will occur later because of staff turnover as a result of retirements.

One important aspect is the influence of the language in teaching. Lecturers and professors are positions, which in Sweden typically include teaching responsibilities. Thus, universities may place expectations on the staff to be able to teach in Swedish, putting some individuals with non-Swedish backgrounds in a more difficult situation in recruitment and promotion compared to individuals with a Swedish background.

However, the language of English has had a very strong status in Swedish higher education and research (Salö 2010). A recent study shows that the position of English as a language of instruction in Swedish higher education is growing stronger (Malmström & Pecorari 2022), often attributed to internationalization. Undergraduate education (bachelor-level education) continues to be dominated by Swedish as the language of instruction. However, between 2007 and 2020 the share of all degree programs taught in English rose from 13% to 28%. In master-level courses in 2020, English was the most common language of instruction (53% of all master’s courses were taught in English) (Malmström & Pecorari 2022, 23).

The disciplinary differences are evident. In master-level courses in 2020, English was the most common language of instruction in engineering and technology, natural sciences, and the creative subjects. In natural sciences, the use of English as the language of instruction increased from 59% in 2010 to 74% of the courses in 2020. The trend is similar in engineering and technology where English was used in 80% of the courses in 2020. In the other areas, Swedish continues to be the major language of instruction. In 2020, 44% of master’s level courses in social sciences were offered in English, 31% in humanities, 20% in medicine, and 14% in health care (Malmström & Pecorari 2022, 25–27). However, the trend is that English becomes more used also in these areas. Thus, especially the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), where most programs are already offered in English, are likely to offer employment opportunities for staff who do not fully master Swedish.

Teaching and research staff in career development positions in the hard and soft sciences

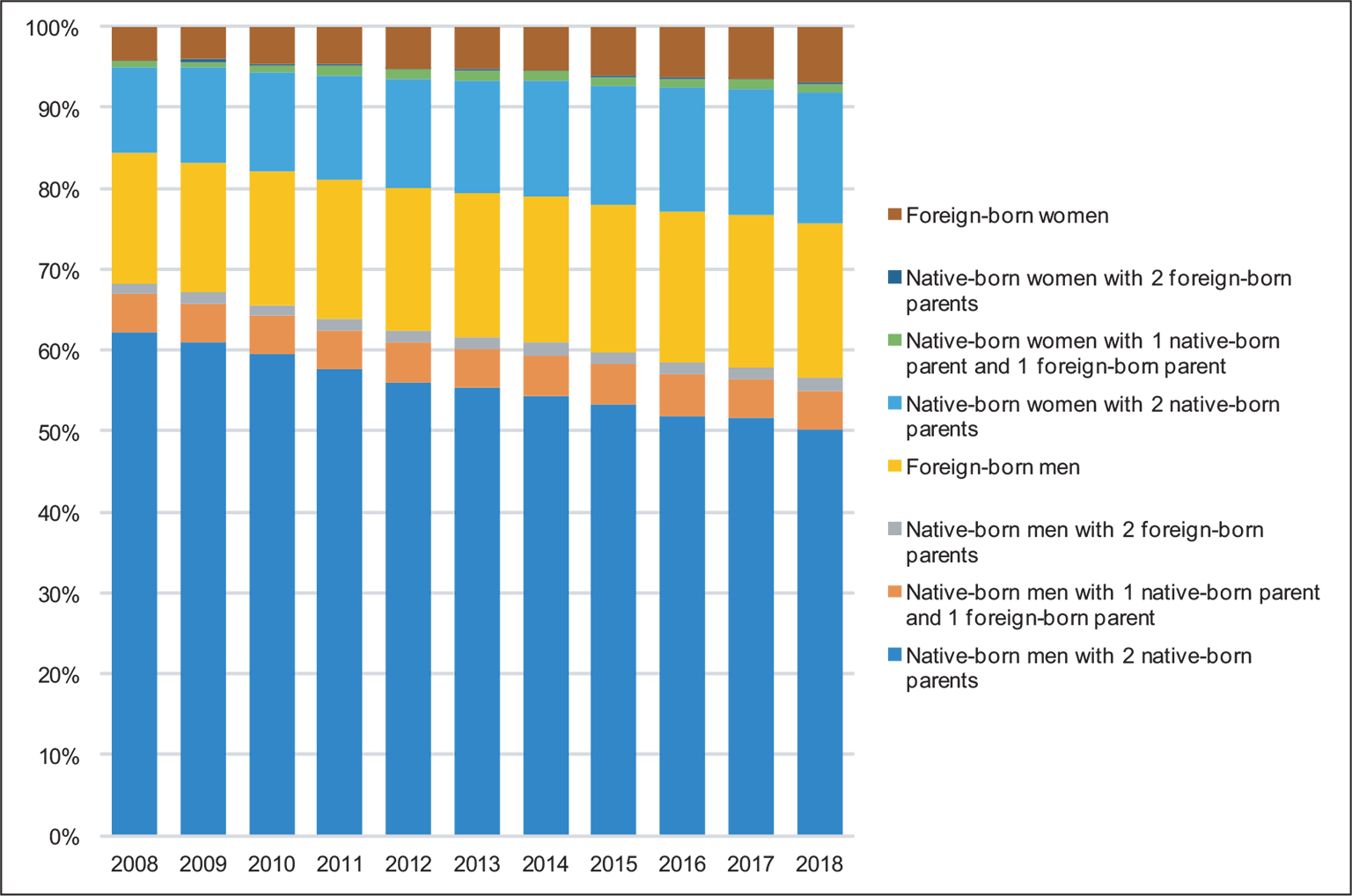

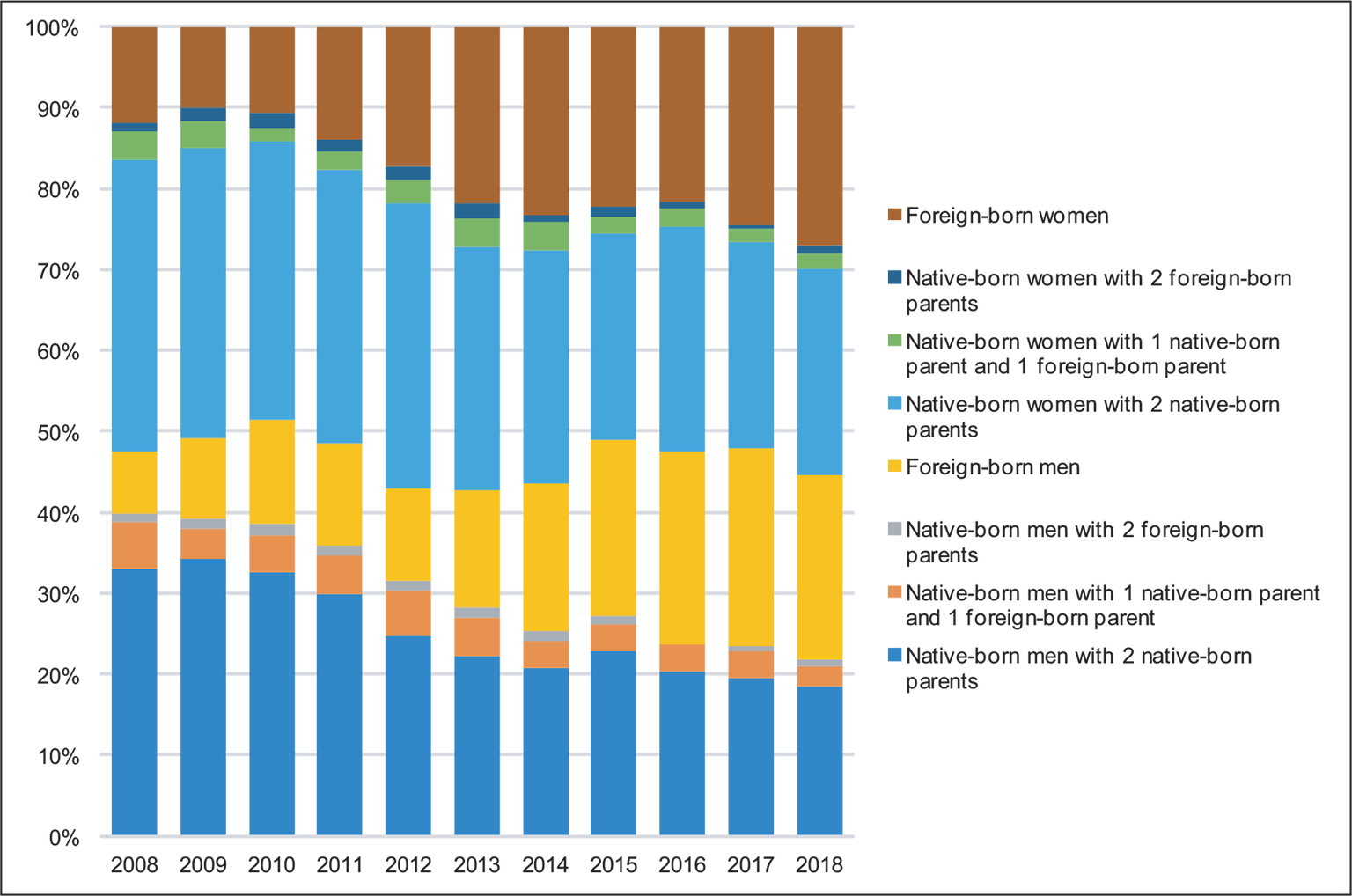

We then move to look at differences in career development positions between the so-called soft and hard sciences (Becher & Trowler 2001). It should be noted that the majority of the career development positions at Swedish universities were located in the hard sciences (1,453 individuals in 2008 and 3,251 individuals in 2018) with much fewer positions in the soft sciences (364 individuals in 2008 and 640 individuals in 2018). The equivalent figures for lecturers and professors are presented in the Appendixes.

Due to the comparatively low number of positions in the soft sciences, there is fluctuation in the composition of staff between the years. Still, the main trend is clear: Figure 4 shows that the share of foreign-born staff increased from 20% in 2008 to 50% in 2018. The trends for the shares of foreign-born women and men were quite similar with some fluctuation over the years. The shares of all native-born groups decreased in the time frame. The share of descendants was between 1% and 3%. However, the low absolute number of positions makes it difficult to identify any clear developments. The share of women increased from 52% in 2008 to 55% in 2018.

The number of positions in the hard sciences was larger, which makes it more meaningful to conduct analysis. Figure 5 shows that overall, the share of foreign-born staff was larger in the hard sciences compared to the soft ones. In the hard sciences, internationalization has been rapid: whereas in 2008 international researchers comprised 35% of staff, in 2013 they represented the majority of staff, and in 2018 their share was 73%. At the same time, the share of all native-born groups has declined. The share of descendants of immigrants has decreased from 2% to 1%, with slightly fewer women in the positions than men.

While the shares of both foreign-born women and men have increased, interestingly the growth rate has been more rapid for foreign-born women than for foreign-born men. Gender balance has remained quite stable, women composing around 44–45% of staff. Thus, it seems that Swedish universities have, in general, been successful in attracting foreign-born women to the hard sciences.

These findings are in line with previous research indicating that mobility differs between disciplinary fields, with more mobility in the hard sciences than in the soft ones (Cañibano & Bozeman 2009). Research has shown that international collaboration and mobility are increasingly important for academic career paths, particularly in STEM fields (Zippel 2011; Vabø 2020). International mobility has become an integral part of researchers’ careers and work lives in these fields, as international experience and networks are often required to be eligible for recruitment (Herschberg et al. 2018). However, our findings also show that the increased recruitment of international staff for career development positions is not a phenomenon exclusive to the hard sciences, but that it represents a more general trend in Swedish academia.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this review show that international recruitment has become important across disciplinary fields at Swedish universities, with an increase of foreign-born staff in all the three job categories investigated. It may be that the research-intensive, fixed-term career development positions at Swedish universities are especially attractive to internationally mobile scholars, who do not necessarily (yet) have family obligations. In career development positions, the increased number of available positions at Swedish universities have opened new job opportunities for international scholars.

However, it is worth noting that the changing composition of staff is not wholly reflected among lecturers and professors, positions that are typically permanent in Swedish academia. Foreign-born staff are found especially in the lower career positions, similar to what has been shown in international research (Smetherham et al. 2010; Khattab & Fenton 2016; Pietilä et al. 2021). The unbalanced situation between categories remains similar to what it was 20 years ago (Swedish Government Commission 2000). Internationalization is not reflected evenly in all the job categories; the changes in positions representing early career stages are not fully reflected in the more prestigious job categories. Our findings indicate a form of “contained diversity” where international recruitment occurs predominantly in time-limited staff categories, whereas the more prestigious academic positions remain dominated by natives. Hence, mobility and international recruitment risk acting as catalysts for stratification within Swedish academia, if the high-profile positions continue to be mainly occupied by natives.

The findings also reveal that while the share of foreign-born staff has increased since 2008, the share of descendants of immigrants remains low, with small changes in all the job categories. This points to the significance of making a distinction within the teaching and research staff with a foreign background, as the developments within the sub-groups are quite different. Overall, the findings call for a separation between the concepts of diversity and internationalization, as they do not necessarily target the same groups or have similar aims as policies (e.g., Erdal & Midtbøen 2018). We argue that higher education and research policies focused on internationalization and diversity need to be investigated and situated within a broader debate on how universities tackle inequalities in the context of the globalization of higher education (Morley et al. 2018). From a social justice perspective, it needs to be considered not only how to attract “global top talent”, but also how to foster inclusive recruitment.

Many previous studies on academic careers indicate that women are generally less mobile when compared to men (e.g., Elsevier 2020; Jöns 2011; Vabø et al. 2014). Also in the case of Sweden, there are more foreign-born men than women among the teaching and research staff, indicating gendered patterns of mobility. However, the findings show that among career development positions, the growth rate for foreign-born women was slightly steeper than for men. Overall, Swedish universities have been successful in attracting foreign-born women. The share of all women has remained stable over the period in career development positions and increased among lecturers and professors.

We cannot draw any conclusions on the causes of the identified developments based on the changes in the absolute numbers of individuals in academic positions alone. It might be that the changes in the compositions of staff reflect the internationalization of the academic labor markets and increased expectations towards mobility as described above. They might also reflect the universities’ recruitment policies that aim at reaching more international applicants. The developments may also be partly due to decreasing supply of native-born individuals in the academic labor market – it might be that certain academic jobs in the Nordic countries are no longer as attractive to native-born people, especially in fields with flourishing labor markets outside academia (cf. Frølich et al. 2019). Also, the causes of the identified discrepancies between the shares of foreign-born staff in the different job categories call for further research. The role of language requirements, but also the role of uneven access to formal and informal networks, and the existence of discrimination are some of the factors that require more research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is part of the Nordic Centre for Research on Gender Equality in Research and Innovation (NORDICORE). NORDICORE was supported by the NordForsk’s Centre of Excellence funding, program “Gender in the Nordic Research and Innovation Area” (grant number 80713).

REFERENCES

- Altbach, P., & Knight, J. (2007). The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3–4), 290–305.

- Altbach, P., & Teichler, U. (2001). Internationalisation and exchanges in a globalized university. Journal of Studies in International Education, 5(1), 5–25.

- Amirell, S. E. (2021). The end of methodological nationalism: The internationalization of historical research in Sweden since 2000. Scandinavian Journal of History, 47(4), 391–413.

- Bauder, H. (2015). The international mobility of academics: A labour market perspective. International Migration, 53(1), 83–96.

- Becher, T., & Trowler. P. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines. 2nd ed. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Behtoui, A., & Leivestad, H. H. (2019). The “stranger” among Swedish “homo academicus.” Higher Education, 77(2), 213–228.

- Bhopal, K., & Maylor, U. (Eds.) (2014). Educational inequalities: Difference and diversity in schools and higher education. London: Routledge.

- Bryntesson, A., & Börjesson, M. (2019). Internationella studenter i Sverige: Avgiftsreformens påverkan på inflödet av studenter. Delmi-rapport 2019:4, Stockholm: Delegationen för migrationsstudier, 2019.

- Byrd, W. C., Brunn-Bevel, R. J., & Ovink, S. M. (2019). Intersectionality and higher education: Identity and inequality on college campuses. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Cañibano, C., & Bozeman, B. (2009). Curriculum vitae method in science policy and research evaluation: The state-of-the-art. Research Evaluation, 18(2), 86–94.

- Castiello-Gutiérrez, S. (2019). Reframing internationalisation’s values and principles. University World News, 01 March 2019.

- de Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard L., & Egron-Polak, E. (Eds). (2015). Internationalisation of higher education. Brussels: European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies.

- Elsevier (2020). The researcher journey through a gender lens. An examination of research participation, career progression and perceptions across the globe. Elsevier.

- Erdal, M. B., & Midtbøen, A. H. (2018). Det mangfoldige akademiet. Https://khrono.no/student-akademia-akademiet-for-yngre-forskere/det-mangfoldige-akademiet/247096. 6 November 2018.

- Frølich, N., Reiling, R. B., Gunnes, H., Mangset, M., Orupabo, J., Ulvestad, M. E. S., Østbakken, K. M. Lyby, L., & Larsen, E. H. (2019). Attraktive akademiske karrierer? Søkning, rekruttering og mobilitet I UH‐sektoren. NIFU-rapport 2019:10. NIFU.

- Hays-Thomas, R. (2004). Why now? The contemporary focus on managing diversity. In M. S. Stockdale & F. J. Crosby (Eds.), The psychology and management of workplace diversity (pp. 3–30). Blackwell Publishing.

- Herschberg, C., Benschop, Y., & van den Brink, M. (2018). Selecting early‐career researchers: The influence of discourses of internationalisation and excellence on formal and applied selection criteria in academia. Higher Education, 76(5), 807–825.

- Hofstra, B., McFarland, D. A., Smith, S., & Jurgens, D. (2022). Diversifying the professoriate. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 8, 1–26.

- Horst, C., & Erdal, M. (2018). What is diversity? PRIO Policy Brief, 12. Oslo: PRIO.

- Huang, F., Finkelstein, M., & Rostan, M. (Eds.). (2014). The internationalization of the academy: Changes, realities and prospects. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Jöns, H. (2011). Transnational academic mobility and gender. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(2), 183–209.

- Khattab, N., & Fenton, S. (2016). Globalisation of researcher mobility within the UK higher education: Explaining the presence of overseas academics in the UK academia. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 14(4), 528–542.

- Konrad, A. M., Prasad, P., & Pringle, J. (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of workplace diversity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Langford, M., Aguilar-Støen, M. C., Carlson, A., Gross, L., & D’Amico, G. (2019). Fra internasjonalisering til mangfold. Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift, 36(1), 85–93.

- Lundgren, A., Claesson Pipping, G., & Åmossa K. (2018). Ett spel för galleriet? Om anställningsprocesserna i akademin. Sveriges universitetslärare och forskare 2018.

- Malmström, H & Pecorari, D (2022). Language choice and internationalisation: The roles of Swedish and English in research and higher education. Report. Språkrådet (Institutet för språk och folkminnen).

- McNair, T. B., Bensimon, E. M., & Malcom-Piquex, L. (2020). From equity talk to equity walk: Expanding practitioner knowledge for racial justice in higher education. Wiley.

- Morley, L., Alexiadou, N., Garaz, S., González Monteagudo, J., & Taba, M. (2018). Internationalisation and migrant academics: The hidden narratives of mobility. Higher Education, 76(3), 537–554.

- Mählck, P. (2018). Vulnerability, gender and resistance in transnational academic mobility. Tertiary Education and Management, 24, 254–265.

- Mählck, P. (2013). Academic women with migrant background in the global knowledge economy: Bodies, hierarchies and resistance. Women’s Studies International Forum, 36, 65–74.

- OECD (2017). Catching up? Intergenerational mobility and children of immigrants. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288041-en

- Pietilä, M. (2015). Tenure track career system as a strategic instrument for academic leaders. European Journal of Higher Education, 5(4), 371–387.

- Pietilä, M., Drange, I., Silander, C., & Vabø, A. (2021). Gender and globalization of academic labor markets: Research and teaching staff at Nordic universities. Social Inclusion, 9(3), 69–80.

- Salö, L. (2010). Engelska eller svenska? En kartläggning av språksituationen inom högre utbildning och forskning. Language Council of Sweden.

- Shavit, Y., Arum, R., & Gamoran, A. (Eds.) (2007). Stratification in higher education: A comparative study. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Smetherham, C., Fenton, S., & Modood, T. (2010). How global is the UK academic labour market? Globalisation, Societies and Education, 8(3), 411–428.

- Sperduti, V. R. (2017). Internationalization as westernization in higher education. Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education, 9 (Spring), 9–12.

- Statistics Sweden. (2022). New postgraduate students under 65 years of age enrolled in postgraduate education 2011/12–2020/21 by background and sex. www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/education-and-research/higher-education/swedish-and-foreign-background-among-students-and-doctoral-students-in-higher-education/

- Statistics Sweden. (2021). Befolkningsstatistik i sammandrag. www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/pong/tabell-och-diagram/helarsstatistik--riket/befolkningsstatistik-i-sammandrag/

- Statistics Sweden. (2020). Swedish and foreign background among students and doctoral students in higher education 2018/19. UF 19 SM 2001.

- Steine, F. (2023). Hver tredje forsker i norsk akademia er innvandrer. https://www.ssb.no/teknologi-og-innovasjon/forskning-og-innovasjon-i-naeringslivet/statistikk/forskerpersonale/artikler/hver-tredje-forsker-i-norsk-akademia-er-innvandrer. 06 March, 2023. Statistisk sentralbyrå, Statistics Norway.

- Swedish Government Commission. (2018). En strategisk agenda för internationalisering. 31 Januaruy, 2018. SOU 2018:3.

- Swedish Government Commission (2017). Internationalisering av universitet och högskolor. [Internationalization of universities and university colleges]. Stockholm: Department of education Dir 2017:19.

- Swedish Government Commission. (2006). Utbildningens dilemma: Demokratiska ideal och andrafierande praxis. Rapport av Utredningen om makt, integration och strukturell diskriminering. Redaktörer: Lena Sawyer & Masoud Kamali. SOU 2006: 40.

- Swedish Government Bill. (2020). Forskning, frihet, framtid – kunskap och innovation för Sverige. Regeringens proposition 2020/21:60.

- Swedish Government Commission. (2000). Mångfald i högskolan. SOU 2000:47.

- Swedish Higher Education Authority (2020). Internationella rekryteringar vanligast bland yngre forskare. Statistisk analys 2020-04-21/217-20-1. Stockholm: UKÄ.

- Takayama, K., Heimans, S., Amazan, R., & Maniam, V. (2016). Editorial: Doing southern theory: Towards alternative knowledges and knowledge practices in/for education. Special issue editorial introduction. Postcolonial Directions in Education, 5(1), 1–25.

- Vabø, A. (2020). Relevansen av internasjonal rekruttering for arbeidsbetingelser i forskning og høyere utdanning. Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift, 4(1), 34–41.

- Vabø, A., Padilla‐González, L., Waagene, E., & Næss, T. (2014). Gender and faculty internationalization. In F. Huang, M. Finkelstein, & M. Rostan (Eds.), The internationalization of the academy: Changes, realities and prospects (pp. 183–205). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Zippel, K. (2011). How gender neutral are state policies on science and international mobility of academics? Sociologica, 5(1), 1–18.

APPENDIXES