INTRODUCTION

In welfare professions like teaching, healthcare, and law enforcement, a critical task is to engage with individuals who find themselves in vulnerable situations or who undergo intense emotional stress. Such situations underscore the necessity for a professional code of conduct to guide practitioners (see, for example, National Education Association, 2020; The Swedish Police Authority, 2021). This article explores how professional judgement is constructed in students’ reflections across three professional education programmes: teacher education, medical education, and police training. This “cross-professional analysis” (Löfgren & Wieslander, 2020) of student reflections contributes insights into the significance of reflective practice in shaping and advancing ideas around professional judgement within these, and potentially other, welfare professions. Despite the distinctiveness of the professions, they also share several similarities. Comparative studies have previously highlighted parallels, such as how informal institutional settings foster reflection in police and medical education (Rantatalo & Lindberg, 2018), and how norms of collegiality influence and shape ethical judgement in policing and teaching (Löfgren & Wieslander, 2020).

Educators, physicians, and police officers all fall under the umbrella of welfare professionals who are tasked with balancing control and care as inherent aspects of their professional practice. The personal interactions between these professionals and non-professionals – whether students, patients, or citizens – demand a heightened level of professional judgement. These three professional education programmes share similar ideals regarding professional judgement, including self-awareness, empathy, a professional relational approach, and social and ethical assessments (Swedish Council for Higher Education, 1993:100, Annex 2: Professional Qualifications; The Swedish Police Authority, 2022). The ideals depict professional judgement as a compilation of skills and abilities that students are expected to develop, concurrently with establishing a professional code of conduct among their peers throughout their education. Reflective practice plays a pivotal role in cultivating professional judgement and facilitating continuous professional development (Coles, 2002; Copely, 2011; Izadinia, 2013; Jensen et al., 2015; Tripp, 1993). Moreover, these three welfare professions share a notable degree of autonomy and discretion in interpreting and executing both formal and informal decisions (e.g. Evetts, 2010; Lindqvist et al., 2020; Lipsky, 1980; Löfgren & Wieslander, 2020). The process of developing professional judgement holds importance for students’ future careers and is defined, negotiated, and constructed through interactions with colleagues, patients, students, and other groups of non-professionals in both educational and professional contexts.

This article explores how students in professional higher education cultivate professional judgement. The following research questions are addressed:

How do students within different professional education programmes shape their understanding of professional judgement?

How do students discuss the development of professional judgement in relation to others in their professional context (students, parents, patients, etc.)?

PROFESSIONAL REFLECTION AND JUDGEMENT AS SITUATED SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONS IN HIGHER EDUCATION

We draw on a constructionist model to investigate how reflective practice acts as an arena for students to discuss and develop professional judgement, understood here as a social, contextual and interactional process. Both as a practice and as a concept, professional judgement is sensitive to context-specific features, and reflective practice needs to be grounded in a learning culture where students and teachers jointly construct knowledge (Karp & Rantatalo, 2020). There are no simple ways to determine or measure the development of – or the relationship between – professional judgement and reflective practice. We do, however, explore reflective practice as significant for the development of professional judgement, and therefore outline some of the research on reflective practice in the professional educations below.

Since at least the 1980s, reflective practice has been considered a key element in professional education and in developing professional judgement (Coles, 2002; Copely, 2011; Hatton & Smith, 1995; Jensen et al., 2015; Karp & Rantatalo, 2020; Schön, 1983; Tripp, 1993). Reflective practice can potentially offer opportunities for both individual and professional development, and this is often used to complement proficiency elements (Karp & Rantatalo, 2020; Rantatalo & Karp, 2020).

In research on intra-professional educators (e.g. physicians educating physicians), several beneficial pedagogical aspects that encourage reflection have shown to develop professional learning, such as the influence of mentors, using learning portfolios, and learning from past mistakes and successes (Tyler & McKenzie, 2011). For example, in Bergman’s (2017) study on police officers as intra-professional educators, he found that police officers’ pedagogical models were manifested through reflection on practice (cf. Schön, 1983). Similarly, Kelchtermans (2009) argues for professional self understanding and subjective educational theory as central aspects of the professional, interpretative framework of each teacher, where teachers develop this framework through reflective and meaningful interactions in the context that constitutes their work (see, also, de Ruyter & Kole, 2010).

Specific activities can also provide opportunities for student reflection. Portfolio writing has been used within medical education (Driessen et al., 2003) as well as police training (Rantatalo et al., 2020), which encourages systematic reflection and structuring of thoughts and experiences. Furthermore, fiction seminars in medical education allow students to engage in reflective practice, which offers opportunities for them to enhance their perspective-taking abilities and their understanding of others (Rydén Gramner, 2022). Similarly, reflection on scenario-based practice can prepare police students mentally for policing (Sjöberg & Lindgren, 2020).

Additionally, more informal arenas – such as canteen discussions, off-school activities and participation in focus group interviews – can provide opportunities for liminality, or ‘in-betweenness’ of the institutional setting, which supports reflective practice and facilitates the development of professional judgement (Karlsson, 2013; Rantatalo & Lindberg, 2018). Thus, liminality is a way to set oneself aside from the purely formal or informal (Rantatalo & Lindberg, 2018). As an example, Rantatalo and Lindberg’s (2018) case study of police training programmes and medical programmes found that practitioners (who), spaces (where), and activities (what) could create liminality and, thus, facilitate reflection on aspects such as wearing the uniform, or experiencing feelings of being outside the norm (e.g. being female in male-dominated police training). This is also exemplified in student teachers’ field training, as student teachers report a need to modify their professional ideals as a coping strategy to resolve experiences of professional inadequacy when encountering the complexity of teaching work (Lindqvist et al., 2017).

Research also points to potential risks when reflection is placed outside the curricula or classroom teaching, or if the students are left to deal with their thoughts and feelings alone (Bek, 2012, 2020). However, if reflection in professional education is understood simply as a teachable set of behaviours, some researchers also highlight the risk of students becoming ‘reflective zombies’ who perform the correct behaviours without truly reflecting (de la Croix & Veen, 2018). In fact, the same didactic point of departure can, depending on teaching methods, provide opportunities either for deepened critical and theory-based reflection, or for superficial reflection based on anecdotes and personal opinion (Bek, 2020). The latter, non-preferred result, has been linked to the lack of guidance and feedback from educators on students’ reflective practice (Bek, 2020; Gunn, 2010). Therefore, scholars also highlight the need to plan for reflective spaces in the formal educational setting (Sjöberg & Lindgren, 2020), and emphasise that educators have an important role to play in providing students with tools for reflection, and guidance on how these tools can be used (Karp & Rantatalo, 2020).

In sum, the literature on reflective practice in professional education shows the potential for reflection to support the development of professional judgement when conducted in a structured way. However, although a significant amount of research highlights the beneficial outcomes of reflective practice, it is also a pedagogical tool that requires both time and guidance. Therefore, there is a risk that reflection will be left for students to deal with alone, outside the curricula, without guidance or mentoring (Bek, 2012). This raises questions about how students within the different professional education programmes construct professional judgement, and how they discuss the development of professional judgement in relation to others in their professional situation.

METHODOLOGY

The data in this article stem from three distinct studies of professional higher education. Our insights from medical education draw from a research project focusing on seminars where fiction was used as a tool for learning [conducted by Rydén Gramner and Eriksson Barajas]. These seminars comprise around 58 hours of video recordings spanning 36 sessions across two Swedish medical schools (see Rydén Gramner, 2022). As for teacher education [conducted by Wallner], we focus on a study centred on leveraging fiction to teach general didactics to preschool student teachers at a southern Swedish university. Our data encompass eight hours of video and audio documentation, capturing interactions among groups of five or six students during three distinct sessions. Transitioning to police training [conducted by Wieslander], data are gathered from five focus group interviews during the students’ fourth and final semester in the police programme, along with an additional trio of focus group interviews during the probationary service at a police station (their fifth semester) (see Wieslander, 2014). These sessions highlight student discussions about the relationship between social diversity and policing practices.

None of the studies originally aimed at unravelling constructions of professional judgement. However, the theme emerged as a secondary finding in all three studies. Importantly, all three studies adhere to the ethical guidelines set forth by the Swedish Research Council (2017). Participants engaged willingly, with a thorough understanding of their involvement, and their privacy was protected by altering names. Furthermore, the gathered data were strictly used for research purposes.

Our analysis is based on a comprehensive dataset of 52 instances showcasing participant discussions about professional judgement. These instances underwent meticulous transcription, followed by a thematic analysis (drawing inspiration from Braun & Clarke, 2006), aimed at identifying commonalities and disparities in the construction of facets of professional judgement. A recurring pattern in the student dialogues was produced at an initial stage of the analysis, and we labelled it ‘images of reality’: a prominent practice within these discussions about ‘reality’, interestingly, involved students drawing examples from their personal experiences in their chosen professional domains – be it as pupils, patients, or part-time employees – or from what their professional lives would be like after graduation.

One way to trace reflective practice is through notions of time and space, for instance when students refer to themselves in their future role (cf. Rantatalo & Lindberg, 2018), which is why these themes were considered to be of analytical interest. In many of the reflections, the students positioned themselves in alignment with, or in contrast to, established norms or malpractice in their future professions. In such interactions, we categorised utterances about values and professional reflections as professional judgement (these are ideals labelled as professional judgement in the different professions, see Swedish Council for Higher Education, 1993:100, Annex 2: Professional Qualifications; The Swedish Police Authority, 2022). Collections of these discussions were compiled in order to explore them in depth.

In the examples that follow, we show how reflective practice provides opportunities for students to socially construct ideas about professional judgement. These examples have been chosen for their clarity in displaying different dimensions of professional judgement, constructed in and through reflective practice where students discuss aspects of their profession with other students or with a researcher.

CONSTRUCTING PROFESSIONAL JUDGEMENT USING THREE DIMENSIONS: PERSONAL ETHICS, EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS AND PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

In what follows, the analytical results from the three studies are presented to clarify the commonalities between them, using examples from police training, medical education and teacher education. The results show that students construct three different dimensions of professional judgement: personal ethics, where personal, ethical preferences influence the construction of professional judgement and its development over time; educational standards, where experiences of ideals and standards presented in the educational setting are constructed as an essential influence on the development of professional judgement; and professional practice, where the profession – and (possibly imagined) experiences of the profession – impact on participants’ construction of professional judgement to a high degree.

For analytical purposes, and to clarify the results to the reader, the three major building blocks will be discussed separately, although, in the original data, the students’ constructions of professional judgement occur interchangeably, and without clear borders between the themes (see the end of the analysis for an example of how the co-construction of several dimensions is carried out).

PERSONAL ETHICS

In this initial section, we show how personal ethical values impact the construction of professional judgement. In (1), below, a group of police students engage in a conversation about the curriculum. They emphasise that education “should promote understanding of other countries and cultures and international relations”. They all agree that the curriculum falls short in this regard, and Jonas proceeds to dissect the matter:

Example 1. The importance of your own competence.

Focus group 1, police students.

Jonas

(student) [regarding educational goals] It feels like as if there is a little like, like with the fundamental values, that there are some politically nice points, but then it should all be included in reality and that’s not quite how it is. It’s like, it’s a meat grinder this that you go through and then you’re supposed to get the most important tools in the backpack out of it and then it’s … and out, and then you hope that most of those who got through here are fundamentally competent enough in themselves so that it will be OK with the tools you’ve got.

In this example, Jonas compares the educational standards to the core values of police practice. He constructs both policies as utopian, as he deems it impossible to teach them to every single student. Using the metaphor of a “meat grinder”, he describes his view of the education as grinding students down to build them back up – whereby they need to attain “the most important tools in the backpack”. The value of the education, and the students’ expectations of their future police work, primarily depends on each student’s individual basic competence. Jonas hopes that individual competence combined with educational tools will be enough to carry out police work in a pluralistic society. Otherwise, the police may not be able to act out these values sufficiently when confronted with reality. Thus, even though Jonas describes the importance of the educational standards (and, to some degree, professional practice) in his construction of professional judgement, these dimensions are dependent on the individual competence of each student.

In (2), the three police students – Max, Chris and Patrik – talk about the relationship between their education, their subjective interpretation of representatives of their future professional practice, and their own personal ethics, and how to handle these three different dimensions in a professional way.

Example 2. The influence of other people’s personal ethics.

Focus group 2, police students.

Max Especially this thing to not have to work with these kinds, as Chris [says], who have never learnt this [knowledge about other cultures] at all, so a bit of education is also needed at the department, I think, some new ideas. I’m also afraid, as Chris says, of ending up with such a (tired) bastard [who bases their work on prejudice about other ethnic groups].

Chris And they, of course, always have the upper hand in that they’ve been out in reality that much longer. If I say to him: “Hey you, let’s do it like this”, he’s just [raises his eyebrows].

Patrik And he has made a name of himself at the department, and here I come and “Hey, you better stay low key, otherwise I’ll slander you”, principally. Then you’ll end up on the bad side of the whole station.

In (2), the participants discuss how educational standards (or the lack thereof) and personal ethics influence professional judgement. However, in this case, the problem is not linked to other students, but to co-workers in the professional field. The three students articulate the difficulties and limitations they face as new police officers when it comes to enforcing the knowledge-based rules and values that their education provides them with, in a hierarchical professional field that resists change. Thus, the personal ethics of their (imagined) future colleagues are constructed as an influence on their own sense of professional judgement in different ways (for example, not wanting to upset older colleagues who are higher in rank and status, as Patrik argues). In other words, the colleague is constructed as part of the professional practice. The argument revolves primarily around differences in personal ethics between new and senior colleagues, and how the differences affect the professional judgement in the situation at hand.

EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS

In the second section, focus is on how educational standards are put to use in students’ constructions of professional judgement. In (3), five preschool student teachers compare a scene from the film Nobody Owns Me [Swe. Original Mig äger ingen] and a short film they have made themselves as part of a module on intercultural pedagogy; they associate the two scenes to items on the reading list. Parenthesis in citations indicates a piece of talk that is difficult to hear, so it is the analysts’ best guess of what is said.

Example 3. Evolving educational standards.

Preschool teacher students, film discussion seminar.

Karen By comparing these two films, we can see that the power went from only being with the teach… teacher to, it now belonging to everyone who is at the meeting. Guardians, children and teacher. If you go with something…

Lily And [browses] yes, err… [reads] and “This because the teachers are experts” or experts, more interpretive priority, or something like that, but we need (like) maybe not, we can like change it actually, like… it sounds a bit… she writes [reads] “The teachers are experts on interpretive priority for knowledge about children’s development, education and learning, while the parents are experts on their children, which means an acknowledgment of parents as competent actors”, but then you can only write, eh, that the teachers are experts on, on knowledge about children’s development, education, learning, right? You need to take interpretive priority (there), right?

Later, their discussion continues:

Example 3, cont.

Astrid Yes but, eh, then… ah, eh, I think in the first film [the film – Nobody Owns Me] you exclude, like, the parents, while and here [the film, students’ own illustration] you invite, like, instead, so that I guess you could write about, that’s what’s the change or the difference.

Rachel Yes, exactly, because we also want (to keep) the difference.

Lily Yes, transfer, you can also like call it, instead of shifting, so maybe it’s understood better.

Astrid Yes, or using your knowledge then to, instead of excluding, inviting in (there), you can, like, also (talk) knowledge, too.

Karen But I think since they write about a shift in power, so maybe you should just mention that.

In (3), the preschool student teachers discuss the collaboration between teachers and parents. They adopt a historical perspective (the plot is set in the 1970s), and compare a scene from the film (a school meeting between parents and an authoritative teacher), to a scene that they have created themselves (in which the parents are given agency and recognition in their roles as knowledgeable about their child). The students explicitly quote from their reading list to construct and retrieve different kinds of knowledge from the roles in the scene. The fictitious example from the film helps them to situate this knowledge in a professional setting.

A combination of educational tools is at work here: the group discussion and peer knowledge, the educational materials of the film, and the course literature. By using the educational tools, the students manage to reposition the parents from controlled and dominated as in the original film, to knowledgeable and with agency in their own production.

The judgement that the students draw on is to actively involve parents and to rely on their expertise. Here, they signify a ‘change’ in perspective taking place over time, constructing their professional judgement as something that is based on learning from historical mistakes, which the film helps them to situate and the course literature helps them to verbalise. Thus, we can see how the educational standards are drawn upon and how they are constructed as an important influence on the students’ professional judgement.

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

In the third section, we show how the participants construct professional practice as an influence on their professional judgement. Below, police student Chris talks about his upcoming field practice as a police officer.

Example 4. The practical field is a little jungle of decision-making.

Focus group 2, police students.

Chris I feel that what will become a little jungle during the apprenticeship, it’s this thing about understanding what you’ve learnt that builds on that you think it’s important when you come out and what’s more practical police work. Because you will have, like, all the respect for [older] people who know how to prioritise how you work and what will be important. But somewhere there will be a situation where you actually maybe know best and have the best knowledge about the law and why it’s important, where you should be able to stand firm. And err… I feel that will be a bloody challenge. And you will probably be like before “But shit, this is important”, and then you realise that OK, in practice this is really, really tough.

Chris explains how the moral values and ethical perspectives students acquire during their professional education connect to the complex world of police practice, “the moral and ethical ‘jungle’ of police practice” they will step into. Essentially, he is discussing how the educational standards will inevitably interact with the professional practice in complex and unpredictable ways.

In Chris’s imagined future of becoming a practising police officer, both educational standards and personal ethics will form a theoretical part of his professional judgement, but this formation will be decidedly situated in and shaped by professional practice: “… in practice, this [linking personal ethics and educational standards with professional practice] is really, really tough”. At the same time, Chris states that there “will be a situation where you actually maybe know best … where you should be able to stand firm” – where the personal ethics and educational standards of the individual police officer will demand great courage in refusing to let the professional practice, represented by more experienced but less knowledgeable colleagues, influence professional judgement. This example highlights the complexity and the dynamic processes imbedded in the practical implementation of professional judgement.

COMBINING DIFFERENT PROFESSIONAL DIMENSIONS

In the fourth section, we will show how the three dimensions of personal ethics, educational standards and professional practice, come into play simultaneously: in (5) a first-year medical student group and their educator discuss how fiction, a novel in this case, can serve as an educational tool.

Example 5. I guess you’ll learn somehow.

Medical education fiction seminar. Novel: My Sister’s Keeper

Eva But I think, like, it was really good to read these kinds of books, because, like, I think fiction books, it’s good because it’s these kinds of dilemmas that we (will) meet later, as physicians. To start right now, like, well, to think about this, and you think, like, it’s really sad, but then you realise that you have, like, after all, chosen the kind of profession that, like, it’s real… umm, really sad sometimes, and then, umm, it’s a matter of you’ll, like, be able to handle it and, it…

Tom Yeah, that’s right.

Inga Mhm

Eva … yeah… it’s, like, hard to know how you will handle it, but you should, well, think that you go in, like that it’s a job too – a profession – I guess you’ll learn somehow.

Tom Yes, and therefore, like, this particular book can be good then, where you see it from different perspectives. We might learn as physicians, to see the problem from different perspectives. Why do the parents act the way they do, for example?

In this example, the medical students discuss the difficult emotional situations they will face as physicians. Just like the student teachers in (3), Eva stresses the importance of learning from fiction as it prepares her for the challenging emotional tasks that she will meet in her future profession. However, both she and Tom seem to view what they retrieve from the novel as something different from their educational learning experiences. They both end up describing learning good judgement as something that happens through practical experience (not through reading novels). Tom also emphasises that it is learning in situ, in the workplace, that impacts substantially on students’ development of perspective-taking and understanding what patients and relatives experience. So, despite (5) illustrating how students construct professional emotional strategies as something they acquire through their education (for instance, by discussing fiction and participating in reflective practice), they counterbalance these views with the belief that they will also need to acquire this knowledge in the future, through real-life experiences in their professional practice.

Eva concludes that she expects to learn the necessary skills to handle the situations in (5) through experiences of professional practice as a physician. One interesting point is that Eva constructs her own attitude towards her occupation (her personal ethics) as an important factor in this process – to be able to view being a doctor as “a job too – a profession”, in contrast to it being something else (perhaps a calling), in other words emphasising the importance of a practice perspective, rather than a personal one (where a physician risks being emotionally compromised).

In (6), we revisit the preschool student teachers from (3), who continue to talk about film as a means to discuss different values in relation to collaboration and communication between preschool and its collaborative partners.

Example 6. The different demands of the professional practice.

Preschool student teachers, film discussion seminar.

Karen Regardless, I think, if there are no scenes from school here [in the film], I believe that at school as a teacher, or a preschool teach- you probably notice if something is a bit off. How does cooperation work, then? Because you maybe notice anyway, well, the daughter is doing really well and maybe. Now none of us have seen this or read anything, but you can, like, think that, well, she might be doing really well and then it’s like this too.

Astrid Mhm. That’s what I meant, like this thing with the child’s best interests.

Karen Well exactly, because then you end up in a dilemma because from the child’s point of view she might be doing really well, and then you don’t want to just take away- her mum has abandoned her, should we also take the father away?

Rachel No, exactly.

In (6), the students are talking about a fictitious situation involving an alcoholic parent and their relationship with the school. Karen argues that “as a teacher … you probably notice if something is a bit off”. One way of understanding this utterance is that the students are confronted with a fictional child living under poor conditions, and they seek different ways to explain why nothing is being done to help the child – which their education and previous experiences tell them should ensue in this case. Thus, they first establish that the teacher (about whom they have no information from the synopsis of the film) is probably aware of the situation (as a professional). Since the teacher, or the school in general, has not acted on the available information about the child, the situation could not possibly be that bad. As professionals, they have a duty to act in the best interests of the child, but it could be difficult to ascertain what these best interests are – and the participants demonstrate how the professional practice can be difficult to navigate. This frames an idea of how the professional judgement of teachers, in relation to children’s well-being, depends on the combination of a teacher’s personal ethics and their management of professional practice. From their perspective as student teachers, it places the teacher as being knowledgeable, and different from the students as not-yet teachers. Throughout the example, the students emphasise these communicative and relational skills, being able to ‘read’ situations and people, as something that a teacher ‘has’.

The professional judgement of teachers is presented in (6) as a balancing act between the professional authority of teachers to serve as protectors of children, and the individual assessments of teachers in these types of cases where the teacher communicates with the home and knows the parties involved, balancing the different demands of professional practice and personal ethics (cf. Löfgren & Wieslander, 2020).

ANALYTICAL CONCLUSIONS

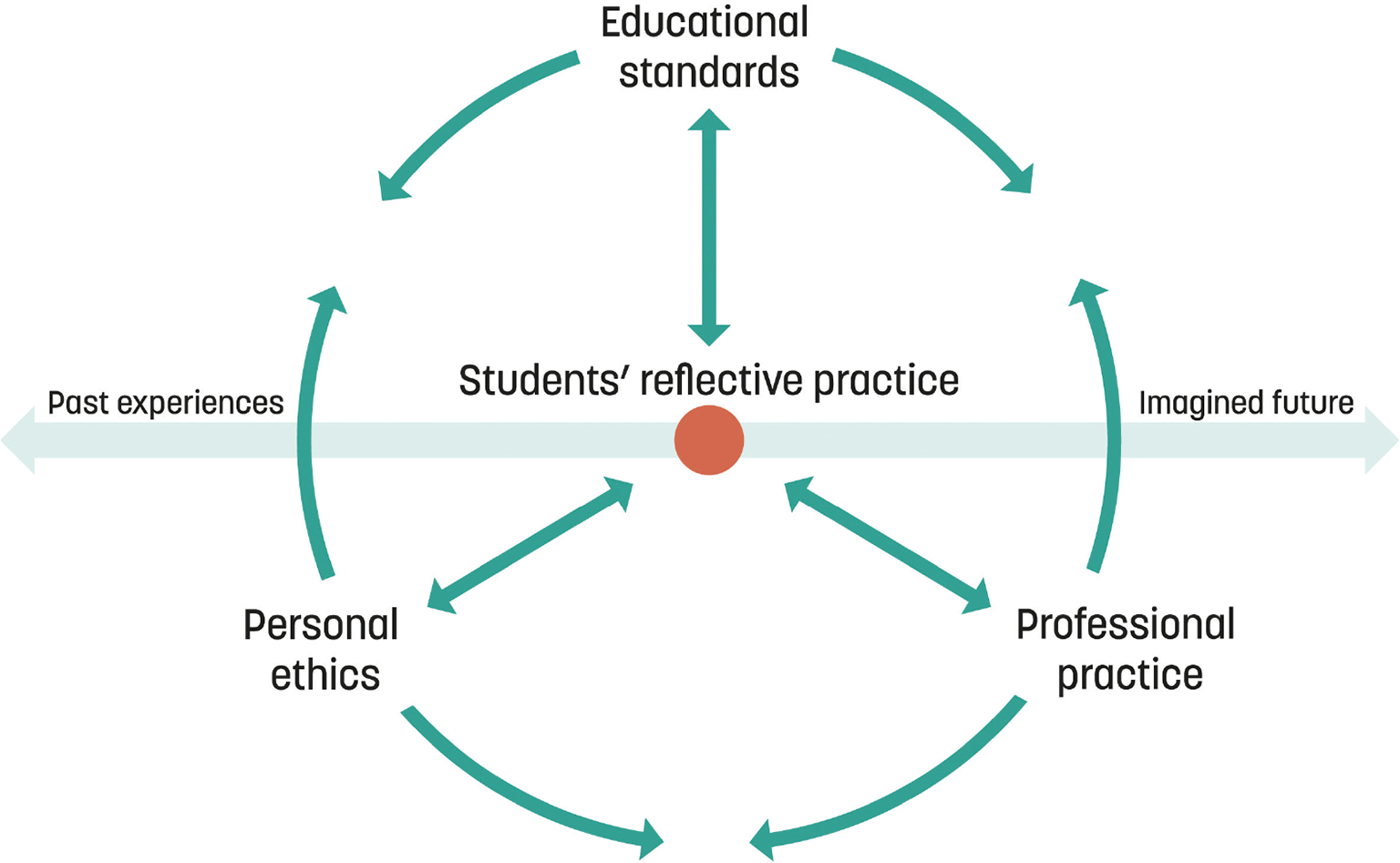

The construction of professional judgement, as proposed in this study, consists of participants drawing on three dimensions: the personal ethics of individuals, the educational standards conveyed through their education, and the professional practice of the chosen field. We argue that these three dimensions are all important as interactional resources utilised by informants to construct and discuss professional judgement in different ways (see Figure 1). Throughout the analysis, we have shown how educational standards influence students’ reflections through educational materials, values, teaching practices, etc. Professional practice, in turn, is constructed as influential in that (imagined) future colleagues, the practical circumstances of the workplace, etc. affect which opportunities students view as available to them. Furthermore, the professional practice is also seen as a sphere of knowledge where students learn, supplementing possible shortcomings in their education, i.e. ‘learning on the job’. Meanwhile, personal ethics is something that students are considered to have when beginning their education. These can then, ideally, be developed or otherwise utilised (or possibly be used as a crutch to get them through the education), but can also act as a harmful influence from other professionals in the field – limiting what students learn through their education.

These three dimensions are then further related to a time perspective, wherein students reach into their past experiences of their own personal ethics, their education, and the profession they are about to enter, as well as their projections of possible future situations they may encounter as practising professionals, where their personal ethics and their experiences from educational and professional settings will be relevant. Thus, the three dimensions are seen as influential reflective resources for students to draw upon in their construction – and development – of professional judgement.

Figure 1. The dimensions of professional judgement in students’ reflective practices.

DISCUSSION

In the educational situations presented in this article, participants utilise three dimensions of professional judgement to discuss with their peers: personal ethics, educational standards, and professional practice – drawing on examples from past experiences and from imagined future experiences. In the observed examples from teacher education, medical education or police training, professional judgement was not taught explicitly, nor was it evaluated or assessed. The examples show that it is the students themselves who initiate and construct aspects of professional judgement through reflective practice, in social collaboration with teachers and other students (cf. Kelchtermans, 2009).

We suggest that it is the process of collaborative reflection that forges professional judgement, and that it is constructed through the students relating and evaluating educational and practical knowledge, individually, as well as in discussions focused on professional practice. The analysis illustrates how students learn to reflect by discussing fictional as well as authentic cases, and by participating in interview situations. The different discussions and situations that arise in these examples demonstrate how students find ways of making professional judgement relevant, no matter the topic at hand (cf. Beaty, 1998). Perhaps it would be beneficial for professional higher education programmes to focus more explicitly on these issues.

This study shows how students construct professional judgement informed by, or dependent on, the professional values of practitioners within each field. Monrouxe (2010) claims that professional identity, in which professional judgement forms a part, is challenged, negotiated and reshaped through identification with the future profession and with professional ethics and values inherent in the concept of a ‘professional-to-be’. However, the students in our examples sometimes resist identifying with professionals in their field. These are currently active professionals whom the students portray as cynical and as carriers of outdated values (cf. Lindqvist et al., 2021; Wieslander, 2014). In opposition to such constructs, the students position themselves as the ‘guardians of professional judgement’. In this way, students sometimes form their understanding of professional judgement through identification with an idealised image of a professional person, rather than more realistic examples.

We suggest that in our data, professional judgement is constructed as an ability developed over time. The student teachers refer to it as an ability that a teacher has, but in their discussions they never problematise how the ability is developed. Thus, there seems to be a view that professional experience, and personal experience could all contribute to this development of professional judgement, but the students in our data sets are not always able to pinpoint how this is done. For example, the medical student Eva, in (5), supposes that they will learn professional judgement “somehow”. One study by Lindqvist et al. (2017) showed that, early in their professional career, student teachers discuss only being able to resolve feelings of professional inadequacy by gaining more experience. This means that students reflect on the role of experience as a mediating factor when coping with emotional challenges, and then highlight the importance of professional experience in developing their own professional skillset – putting an emphasis on the dimension of practical experience, rather than academic experiences or personal ethics. However, as Beaty argues: “Experience alone does not guarantee teaching quality, nor the emergence of a professional approach to teaching. Development takes more effort than that” (1998, p. 99). The indeterminateness that comes with reflection on uncertainties in their future profession is argued to be both problematic and a state of potential (Rantatalo & Lindberg, 2018). Being a problem-driven process, even the most informal reflective situations by students in liminal spaces are argued to be important for learning (Rantatalo & Lindberg, 2018) – adding to the benefits of professional experiences demonstrated by Lindqvist et al. (2017). This strengthens the importance of structured reflective practice, where educators play an important role in giving feedback and connecting reflections to educational standards, rather than letting reflective practice simply consist of students’ personal opinions and anecdotes (cf. Bek, 2012, 2020). Reflective practice, which connects educational and professional theory with professional practice and personal ethics, could reinforce student agency when it comes to professional judgement, and minimise the risk of leaving students paralysed to act due to perceptions of a professional culture that is slow to change.

A concluding argument from this article is that even if the skills connected to professional judgement seem to be rarely evaluated and examined in higher education, they are at least explored in ongoing reflective activities. Professional judgement seems not to be a matter of tacit knowledge (cf. Polanyi, 2015), in the way that the cyclist cannot put into words how they keep their balance, or the swimmer how they keep themselves afloat. Rather, part of the professionality of the three examined groups is the very fact that judgement, ethics, relational development and other aspects are thoroughly examined and re-examined in professional life. In these cases, education seemingly offers students a chance to examine the central aspects of professional judgement, to practise critical reflection, to try and fail, and ultimately to explore and develop their own personal professional judgement in an environment surrounded by peers. Thus, what our study demonstrates is the importance not only of keeping this process alive in professional education, but also nurturing it and letting it grow – of encouraging these types of reflection among students in all facets of their education.

REFERENCES

- Beaty, L. (1998). The professional development of teachers in higher education: Structures, methods and responsibilities. Innovations in Education and Training International, 35(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/1355800980350203

- Bek, A. (2012). Undervisning och reflektion: om undervisning och förutsättningar för studenters reflektion mot bakgrund av teorier om erfarenhetslärande [Teaching and reflection: on teaching and conditions for student reflection on the background of theories on experience teaching]. [Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University]. Umeå University.

- Bek, A. (2020). Undervisning för reflektion: Lärdomar från kommunikativt förhållningssätt och praktikuppföljning [Teaching for reflection: Lessons from a communicative approach and practice reflections]. In S. Karp & O. Rantatalo (Eds.), Reflektion som professionsverktyg inom polisen [Reflection as a professional tool in the police] (pp. 66–78). Umeå University.

- Bergman, B. (2017). Reflexivity in Police Education. Nordisk Politiforskning, 4(1), 68–88. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1894-8693-2017-01-06

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Coles, C. (2002). Developing professional judgement. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 22(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340220102

- Copely, S. (2011). Reflective practice for policing students. Learning Matters.

- de la Croix, A., & Veen, M. (2018). The reflective zombie: problematizing the conceptual framework of reflection in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 7(6), 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0479-9

- de Ruyter, D. J., & Kole, J. J. (2010). Our teachers want to be the best: on the necessity of intra professional reflection about moral ideals of teaching. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 16(2), 207–2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600903478474

- Driessen, E., van Tartwijk, J., Vermunt, J., & van der Vleuten, C. (2003). Use of portfolios in early undergraduate medical training. Medical teacher, 25(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159021000061378

- Evetts, J. (2010). Reconnecting professional occupations with professional organizations: Risks and opportunities. In G. Svensson & J. Evetts (Eds.), Sociology of professions: Continental and Anglo-Saxon traditions (pp. 123–144). Daidalos.

- Gunn, C. L. (2010). Exploring MATESOL student “resistance” to reflection. Language Teaching Research, 14, 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810363940

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U

- Izadinia, M. (2013). A review of research on student teachers’ professional identity. British Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 694–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2012.679614

- Jensen, E., Skibsted, E. B., & Christensen, M. V. (2015). Educating teachers focusing on the development of reflective and relational competences. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 14(1), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-015-9185-0

- Karlsson, M. (2013). Emotional identification with teacher identities in student teachers’ narrative interaction. European Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2012.686994

- Karp, S., & Rantatalo, O. (Eds.). (2020). Reflektion som professionsverktyg inom polisen [Reflection as a professional tool in the police]. Umeå University.

- Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who I am in how I teach is the message: self understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 15(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875332

- Lindqvist, H., Thornberg, R., & Colnerud, G. (2020). Ethical dilemmas at work placements in teacher education. Teaching Education, 32(4), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2020.1779210

- Lindqvist, H., Thornberg, R., Weurlander, M., & Wernerson, A. (2021). Change advocacy: Student teachers and beginning teachers coping with emotionally challenging situations. Teachers and Teaching: Theory & Practice, 27(6), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1889496

- Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Resolving feelings of professional inadequacy: Student teachers’ coping with distressful situations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64(1), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Sage.

- Löfgren, H., & Wieslander, M. (2020). A Cross-professional Analysis of Collegiality Among Teachers and Police Officers. Professions and professionalism, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.3493

- Monrouxe, L. V. (2010). Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Medical Education, 44(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x

- National Education Association. (2020). Code of Ethics for Educators. https://www.nea.org/resource-library/code-ethics-educators

- Polanyi, M. (2015). Personal knowledge: towards a post-critical philosophy. University of Chicago Press.

- Rantatalo, O., Ghazinour, M., & Padyab, M. (2020). Erfarenheter och effekter av reflektionsinriktad portfoliometod [Experiences and effects of reflection-based portfolio method]. In S. Karp & O. Rantatalo (Eds.), Reflektion som professionsverktyg inom polisen [Reflection as a professional tool in the police] (pp. 53–63). Umeå University.

- Rantatalo, O., & Karp, S. (2020). Forskning om reflektion inom polisen – en översikt [Research on reflection in the police – an overview]. In S. Karp & O. Rantatalo (Eds.), Reflektion som professionsverktyg inom polisen [Reflection as a professional tool in the police] (pp. 28–41). Umeå University.

- Rantatalo, O., & Lindberg, O. (2018). Liminal practice and reflection in professional education: police education and medical education. Studies in Continuing Education, 40(3), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1447918

- Rydén Gramner, A. (2022). Cold Heart, Warm Heart: On fiction, interaction, and emotion in medical education [Doctoral dissertation, Linköping University]. Linköping University. https://doi.org/10.3384/9789179292355

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Sjöberg, D., & Lindgren, C. (2020). Modeller för reflektion i scenarioträning: erfarenheter från övningar med studenter och yrkesverksamma [Models for reflection in scenario training: experiences from exercises with students and professionals]. In S. Karp & O. Rantatalo (Eds.), Reflektion som professionsverktyg inom polisen [Reflection as a professional tool in the police] (pp. 111–120). Umeå University.

- Swedish Council for Higher Education. (1993:100). The Higher Education Ordinance.

- Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good Research Practice (2nd ed.). https://www.vr.se/download/18.5639980c162791bbfe697882/1555334908942/Good-Research-Practice_VR_2017.pdf

- The Swedish Police Authority. (2021). Polismyndighetens etiska råd [The Ethical Council of the Police Authority]. https://polisen.se/om-polisen/organisation/polismyndighetens-etiska-rad/

- The Swedish Police Authority. (2022). Utbildningsplan för polisprogrammet [Educational plan for the police programme]. The Swedish Police Authority.

- Tripp, D. (1993). Critical Incidents in Teaching: Developing Professional Judgement. Routledge.

- Tyler, M. A., & McKenzie, W. E. (2011). Mentoring first year police constables: Police mentors’ perspectives. Journal of Workplace Learning, 23(8), 518–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621111174870

- Wieslander, M. (2014). Ordningsmakter inom ordningsmakten: Diskurskamp, dilemma och motstånd i blivande polisers samtal om mångfald [Forces in the Police Force: discursive conflict, dilemmas and resistance in Police Trainee discourse on diversity]. [Doctoral dissertation, Karlstad University]. Karlstad University.